This article was originally published by Political Violence at a Glance on 4 March 2020.

Many states have long relied on various forms of information control, such as surveillance and censorship, as part of their approach to governance. With the development of advanced digital technologies, states have new tools to monitor citizens, restrict communication, and manipulate information. While observers have expressed concerns that information control violates human rights and suppresses citizen influence in governance, the Covid-19 virus highlights another area where government information suppression can have pernicious consequences: public health.

In the initial phase of the Covid-19 outbreak, the Chinese government silenced whistle-blowers, expelled and disappeared journalists, and revised Covid-19 counts. Many argue that the disease spread more rapidly and was more deadly because citizens were unaware of the risks. As the discrepancy between the government’s rhetoric and its actions became clear, a parallel reality of fake claims about the virus arose on social media.

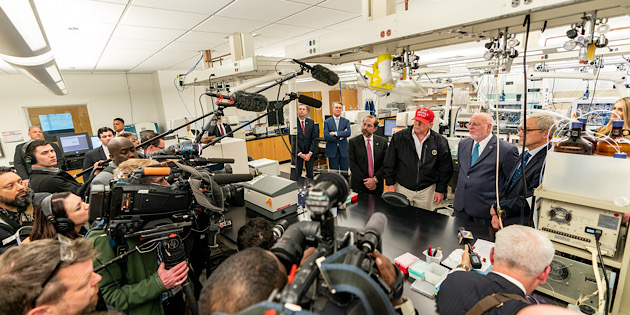

At the center of both the pandemic threat and the “infodemic” is a breakdown in trust. China’s suppression and falsification of information about the virus inhibited containment. It also led citizens to distrust official statements and seek answers online. Rumors and conspiracy theories fueled hoarding, putting additional strains on government resources and containment efforts. A similar cycle is taking place in Iran, where the government’s response has included denial, dishonesty, and shifting the blame to Trump. The result: Iranian citizens don’t know what information to trust. In the US, Trump’s inaccurate statements and conjectures about plots against him call into question the government’s accountability and escalate global concerns.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. Evidence from China and Germany in the weeks before the 1989 revolution, has shown how state censorship weakens government legitimacy and induces alternative information-seeking. Governments in autocratic countries are more likely to exploit these tools in ways that violate human rights, but information control also raises concerns in democracies. In an online study that we conducted in Japan, we find that when citizens fear that the government is watching what they do online they are more likely to log off. Other studies have found that the US mass surveillance program under the NSA caused Internet users to question their privacy, leading to self-censorship and truncating internet searches.

There is a bitter upshot to the Covid-19 affair. It is clear that China’s information control measures have backfired: with the death of whistleblower doctor Li Wenliang came a rare outpouring of demands for free speech. Chinese crowdsourcers are fighting both censorship and misinformation through fact-checking, screenshots, and chatroom newsgroups, and defying surveillance by using secure messaging apps. Social media companies such as Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and TikTok have taken steps to tackle false claims and direct users to accurate information. The global spread of the virus has spurred international condemnation of China’s censorship regime.

Information freedom is enormously valuable—the pandemic threat has made that painfully clear. WHO operational planning guidelines specify that governments need to enable two-way channels for public information and feedback mechanisms in order to facilitate rapid reaction responses. Public health professions and epidemic experts also emphasize the importance of trust: mixed-messages and attempts to mislead the public sow confusion and panic, while the dissemination of evidence-based information can secure public cooperation with government directives.

Some non-democratic states have seen the wisdom in freely sharing accurate information with the public. Singapore, for example, opted not to restrict public discourse, and that policy seems to have served the country well, having thus far prevented widespread local contagion despite imported cases and its status as a regional air traffic hub. As the number of countries hosting Covid-19 rises, protecting public health requires that governments actively resist the temptation to control the flow of information, and take steps to remove any remaining barriers to information freedom.

About the Authors

Kristine Eck is an Associate Professor at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University.

Sophia Hatz is a Post-doctoral Researcher at the Department of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.