This article was originally published by The International Crisis Group on 6 June 2016.

Venezuela is a country of almost 900,000 square kilometres with over 30 million inhabitants. But a few, run-down city blocks in the west of the capital, Caracas, carry a significance far beyond their size and population. Known as “el centro”, this part of Libertador municipality holds the presidential Miraflores palace, many ministry buildings, the Supreme Court (Tribunal Supremo de Justicia, or TSJ) and the headquarters of the electoral authority (Consejo Nacional Electoral, or CNE). In the past few days “el centro” has been the scene of a variety of events that speak volumes about the depth of the combined political, economic, social and humanitarian conflict that seems finally to have caught the attention of the wider world. And about the difficulty of resolving it through dialogue.

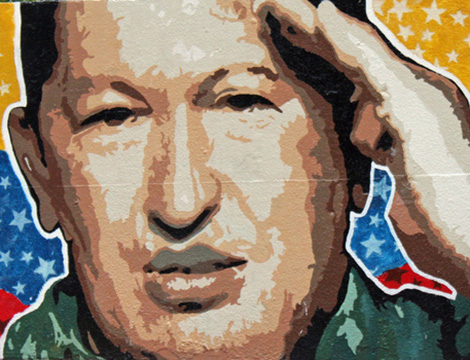

Crisis Group has for years warned that authoritarian governance, economic mismanagement, violent crime and lawlessness in Venezuela would eventually prove a toxic combination. The crisis spiralled out of control following the untimely death from cancer of the country’s charismatic leader Hugo Chávez in 2013 and the near simultaneous plunge in the price of oil, on which the economy is almost wholly dependent. Acute shortages of food, triple-digit inflation, one of the world’s highest homicide rates and the collapse of public services, including health care, are signs of deeper dysfunction. This is a country on the verge of implosion.

In December, the opposition Democratic Unity (MUD) alliance gained control of the country’s legislative body, the National Assembly. Although President Nicolás Maduro recognised the result, he has since used his control of other branches of government – particularly the judiciary – to block every parliamentary initiative and strip the Assembly of many of its constitutional powers. On 13 May, he decreed a wide-ranging state of emergency, a move that was declared constitutional by the Supreme Court despite being vetoed by parliament. The Assembly, Maduro says, has outlived its usefulness, and he is threatening to jail its leaders for treason.

The MUD is now attempting to use a provision of the 1999 constitution, introduced by Chávez himself, which allows a recall referendum against elected officials. In order to do so, under rules drafted by the CNE after Chávez was almost unseated in this way in 2004, referendum supporters must first obtain the signatures of 1 per cent of the electorate. Once these signatures are validated, the opposition needs 20 per cent of voters to request the referendum itself.

However, the government-controlled CNE took almost two months just to provide forms for the first batch of signatures. It has invented absurd new pretexts for ruling signatures invalid, and repeatedly cancelled meetings with the opposition leadership. Although the MUD handed in some two million signatures – more than ten times the number required – even if these were accepted as valid, that would only trigger the second signature drive, not the vote itself.

The government insists there is no time to hold the referendum this year. If it succeeds in delaying a vote until mid-January, the constitution allows the vice president to serve out the remaining two years of the presidential term. Polls suggest almost three quarters of the electorate want Maduro to leave office this year. A referendum in 2017 would allow the ruling United Socialist Party (PSUV) and its military allies to dump the unpopular president but hang on to power.

On 31 May, Luis Almagro, secretary general of the Organization of American States (OAS), published a devastating, 132-page report on the Venezuelan crisis. His conclusion: that there have been “serious disruptions of the democratic order” in Venezuela, requiring the OAS to activate the Inter American Democratic Charter. Almagro wrote that “the fate of democracy in Venezuela” hangs on holding a recall referendum this year. However, a meeting the following day of the OAS permanent council, comprising the ambassadors of member states, agreed only to support a tentative dialogue initiative facilitated by former heads of state and government regarded by the MUD as sympathetic to Maduro. Activation of the Charter, which could ultimately lead to the suspension of Venezuela from the OAS, remains pending.

The government declared the OAS resolution a victory. However, so did the opposition, which cited the resolution’s emphasis on the importance of “full respect of human rights” and “the consolidation of representative democracy”. President Maduro called Almagro “trash” and told him to “shove the Charter wherever it fits best”. Meanwhile, on the streets of “el centro”, the drama that is everyday life took another turn for the worse.

Under the state of emergency decree, Maduro is empowered to do whatever he deems necessary to ensure the adequate distribution of food and other basic goods. Military and civilian loyalists, often armed, are authorised to requisition food and distribute it via a newly invented network of popular committees known as CLAPs (Local Supply and Production Committees). The CLAPs are drawn from political groups that include the Francisco de Miranda Front (FFM), an armed organisation. The emergency decree charges them with helping “maintain order”. Not surprisingly, the CLAPs have already been accused of corruption and political favouritism.

REPORT | Violence and Politics in Venezuela, 17 August 2011

On 2 June, as hundreds queued on the streets of downtown Caracas, awaiting the arrival of food trucks, the CLAPs announced that no more price-controlled goods would be sold in the stores. The food trucks were diverted to government food depots, supposedly to be distributed door-to-door. The result was an unprecedented confrontation between angry citizens and police and National Guard riot squads, just a few blocks from parliament and the presidential palace. Tear gas was used and a score of journalists covering the clashes were beaten and robbed by armed civilians as the security forces looked on impassively. The confrontation lasted several hours and was joined by students who had been protesting nearby.

Meanwhile, not far away, MUD leaders headed for a scheduled meeting with the CNE board. The electoral authority had promised to finish validating the signatures by 2 June. The next stage would be for signatories to submit to electronic finger-printing at designated centres. The CNE, however, not only failed to activate the next stage, it cancelled the meeting with the MUD – with five minutes’ notice and for the fifth time running. Three months after announcing its intention to activate the recall referendum, the MUD has yet to surmount the first hurdle.

Even more than Maduro himself, one man personifies that hurdle: Jorge Rodríguez, the brother of Foreign Minister Delcy Rodríguez, is a leading member of the PSUV and mayor of Libertador municipality, which covers the whole western half of Caracas. As mayor, he has declared the municipality a “peace zone” in which the constitutional right to peaceful protest is suspended for the opposition. Rodríguez, a former vice president to Chávez and one-time de facto head of the CNE, also chairs an unusual presidential commission. Charged with verifying the referendum signatures on behalf of Maduro, the commission has in effect supplanted the CNE, although it has no legal status. The mayor issues frequent incendiary statements accusing the MUD of falsifying hundreds of thousands of signatures.

When former Spanish premier José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and two former Latin American presidents held exploratory talks with government and opposition representatives in the Dominican Republic in late May, it was Jorge Rodríguez who headed the PSUV delegation, along with his sister the foreign minister. The MUD later accused them of sabotaging the confidential meeting by filtering a distorted account to the official press.

Rodríguez is a member of what has become known as the “Group of Six” – the inner circle of power. If the recall referendum is to be held this year – an event upon which the future of Venezuelan democracy might hinge, according to the OAS secretary general – then the mayor of Libertador will have to be persuaded to stop blocking it.

The first item on the agenda at any future session of talks-about-talks must be the referendum. Continued obstruction of this constitutional provision should trigger the immediate activation of the OAS Democratic Charter.

The situation on the streets of Venezuela is becoming more dangerous by the day. A protracted and inconclusive dialogue will not help, and could make matters worse. The government must be convinced to take immediate steps to avert catastrophe – including to stop blocking attempts to call a referendum, permit the normal functioning of parliament, release all political prisoners, and allow urgently needed international humanitarian aid.

Phil Gunson is the Senior Analyst for the Andes Project at the International Crisis Group.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit our CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Publications.