This article was originally published by E-International Relations on 21 July, 2015.

An old territorial dispute between Venezuela and Guyana has flared up once again as the Guyanese government contracted ExxonMobil to look for offshore oil in an area that Caracas claims as its own. While it is unlikely that this particular instance will escalate into an armed conflict, these tensions highlight how non-violent incidents over coveted resources will continue to occur. Moreover, should clashes over this disputed territory continue, Venezuela will, in this author’s opinion, come out as the loser as it will be inexorably regarded as the aggressor against a militarily weaker neighbor.

Moreover, while this dispute has thankfully been non-violent, it could affect U.S.-Venezuela relations as the two governments have been at odds for over a decade and a half. Washington could capitalize on Venezuela’s aggressive stance in order to strengthen relations with Guyana to better monitor developments in Caracas.

A Brief Overview

A full historical review of the Venezuela-Guyana dispute is beyond the scope of this analysis, but it is necessary to give a basic historical overview to put the current situation in the proper context. Guyana is a former British colony (with Dutch influence), formerly known as British Guyana, which obtained its independence in 1966. However, the area, while it was under London’s control, was at odds with Venezuela due to a territorial dispute that dates back to the 19th century. Venezuela obtained its independence in 1824 from Spain, much earlier than Guyana, and has consistently claimed a portion of present-day Guyana.

London and Caracas reached an agreement via the 1899 International Arbitral Awards (held in Paris) which was thought to have put an end to differences. In 1962, Venezuela declared the 1899 treaty void and returned to its pre-1899 claims. In 1966, the same year that Guyana gained its independence, a Mixed Commission was established to address Venezuela’s renewed demands; but while negotiations took place, the Venezuelan military was accused of carrying out incursions into Guyana’s border territory, including the occupation of the Guyanese half of the Ankoko Island. Negotiations and incidents followed, as well as agreements such as the Protocol of Port of Spain, which Venezuela decided not to renew in 1982.

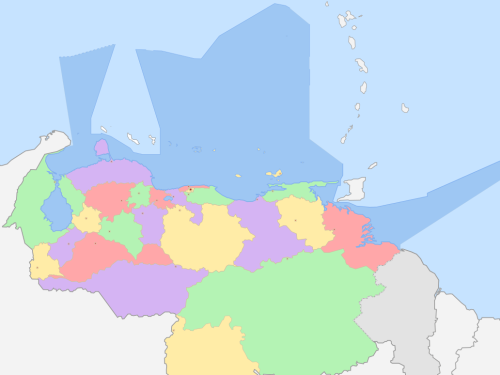

Caracas claims a contested area of around 155 thousand square kilometers in addition to a maritime area off the contested coast.

The dispute generally remained dormant for decades as the 21st century began but resurfaced in November 2007 due to a bizarre incident in which some 30 Venezuelan soldiers entered Guyanese territory and used explosives to destroy two dredges. The Guyanese Defense Forces were deployed to the area, but by that time the Venezuelans had already returned to their country. Fortunately the incident did not escalate into an armed conflict. The Venezuelan government apologized for the incursion as Deputy Minister of External Relations Rodolfo Sanz travelled to Guyana to diffuse the situation. He declared that Caracas “expressed sincere regrets and assured that the incident had no political motive on the part of the Venezuelan Government.”

Another incident occurred on October 2013 when the Venezuelan Navy intercepted the Teknik Perdana, a ship flying Panama’s flag that was hired by the Guyanese government and the Anadarko Petroleum Corporation to carry out seismic investigations. This was a preliminary step for future expeditions to look for offshore oil reserves. Thankfully, like in 2007, the incident did not evolve into a conflict, but the situation does highlight how the two countries began to clash at sea.

The newest round of tensions erupted in March, less than a decade after the Venezuelan military incursion into Guyana and only two years after the Teknik Perdana incident. ExxonMobil started looking for oil through its research vessel, the Deepwater Champion. According to Reuters, “Exxon signed an agreement with Guyana to explore the 26,800 square kilometer block, 100 to 200 miles (160 to 320 km) offshore, in 1999.” On May 20, the company found (black) gold as it announced that it had discovered oil. Days later, the Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro announced that the area in dispute is rightfully Venezuelan. Even more, the Venezuelan presidential decree No. 1.787 (dated May 27) divided Venezuela’s coast into four defense areas. One of them is called the “Zona Operativa de Defensa Integral Maritima Insular Atlantica” (ZODIMAIN Atlantica; Atlantic Operational Maritime & Insular Defense Zone), which extended from the Promonotory of Paria to the border shared with Trinidad & Tobago; hence it included the disputed maritime area between Venezuela and Guyana. In early July, the Venezuelan government took a step backwards by passing the presidential decree No. 1.859 which modified the aforementioned No. 1.787; the new directive withdrew specific coordinates for the ZODIMAINs.

Guyanese President David Granger labeled Venezuela’s claims as a “legal absurdity” and stated that Exxon’s operations will continue. The situation worsened in early June, when the Guyanese government decided to stop flights made by CONVIASA, Venezuela’s state-owned airline. Georgetown officially states that this is due to “the non-payment of bonds and landing fees to the government and the Cheddi Jagan International Airport.” However, it is impossible to deny the obvious coincidence that this drastic measure comes shortly after Venezuela’s claim over Guyanese waters. In retaliation, Caracas called in the Venezuelan ambassador to Guyana in early July and also announced that it will not renew a rice trade agreement with Guyana, which is set to expire in November.

Analysis

At the time of this writing, the possibility of inter-state warfare between Venezuela and Guyana thankfully remains extremely low. The two countries have never gone to war over the territory in dispute, but the aforementioned incidents that occurred in the past decades are problematic since they deteriorate bi-national relations—i.e. the cancellation of CONVIASA’s flights, which left dozens of people, including Venezuelan citizens, stranded in Georgetown. Moreover, in a worst-case scenario, a small incident like a seized vessel could be the trigger that transforms it into a greater conflict if tensions are not properly managed.

One aspect worth stressing is that the 2007 dredges incident brought Guyana onto the U.S. radar. At the time, relations between the U.S. and Venezuela, then led by Presidents George W. Bush and the late Hugo Chávez respectively, were continuing to deteriorate. Caracas had accused Washington of being behind a short-lived coup that briefly removed Chávez from power in April 2002. Meanwhile, Washington was concerned about a Caracas-Moscow alliance, as the Russian government had begun to sell high-tech weapons to the South American state. Thus, Washington saw this incident as a valid reason to have a stronger presence on Venezuela’s eastern flank. For example, military cooperation between the U.S and Guyana increased: The “USS Kearsarge,” a multipurpose amphibious assault ship, made a port call in 2008. Officially, the Pentagon said that this was a humanitarian mission, but at the time IPS News explained how the assumption in Guyana was that the naval visit was “designed to send a tacit political and military signal to neighbouring Venezuela,” particularly as “U.S. military helicopters are flying around communities as close as 16 kilometers from the Venezuelan border.” It makes sense to believe that Washington was capitalizing on Georgetown’s security concerns with its neighbors in order to monitor Venezuela.

Let us look at Venezuela’s geopolitical situation in another way: the country borders three nations, and it has been at odds with two of them in the past decade. Apart from Guyana, Venezuela also has a territorial dispute with neighboring Colombia. Even more, Bogota and Caracas had tense relations during the rule of President Alvaro Uribe and the late President Chavez (respectively) – to the point that in 2008 the two countries almost went to war. Nowadays, relations are much better but Venezuela is still concerned about the fact that Washington remains a steadfast Washington ally. As for Brazil and Venezuela, the two countries have maintained cordial relations and there have not been any security incidents. Finally, Caracas has declared that U.S. aircraft flying from the Forward Operating Location base in Curacao (a Caribbean overseas territory of The Netherlands, just north of Venezuela) were surveillance planes spying on Venezuela.

In other words, Guyana-Venezuela tensions have to be placed in the proper context of Venezuela’s complex relationship with its neighbors, a development that Washington has capitalized on. From Venezuela’s point of view, Washington can be regarded as trying to encroach on the South American state by increasing security ties with its neighbors.

As for the current tensions between Caracas and Georgetown, they come at a time of renewed strained relations between Caracas and Washington. In March, President Barack Obama announced that Venezuela is now considered a “national security threat,” a declaration that brought about economic sanctions on various Venezuelan government officials. At the time of this writing, both sides have been attempting to improve their tense relations, which date back to the Chávez years, as bilateral negotiations recently took place in Haiti. Nevertheless, no major announcement has come out of these talks. Moreover, while there have not been any new U.S. naval deployments to the region, a Guyanese vessel did participate in Tradewinds 2015 (naval exercises organized by the U.S. Southern Command and Caribbean nations).

It is also important to note that Guyana has been rallying its allies in the Caribbean and beyond to support its claims. So far, the Guyanese government has been successful, as in March when the other members of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), a 15-nation bloc of Caribbean states, declared that the organization “reiterates its firm, long-standing and continued support for the maintenance of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Guyana.” The move was probably a blow to Caracas, as most CARICOM members, Guyana included, are members of PETROCARIBE, an alliance whose members purchase oil from Venezuela at reduced costs. These small Caribbean states are very dependent on cheap Venezuelan oil in order to maintain their economies and fulfill their energy needs; however, the latest Venezuela-Guyana incident highlights that they will rally to protect one of their fellow members against an external security threat.

Comparing Naval Forces

Given that the most recent incident has to do with offshore oil discoveries, I will briefly address the naval force of both countries. Guyana is a small nation whose military is called the Guyana Defense Force, and its naval branch is the Guyana Defense Force Coast Guard (GDFCG). While the GDFCG has limited resources at its disposal, it has been upgraded in recent years. In 2014 Guyana received back the flagship “GDFS Essequibo”, which had been sent to Brazil for repairs. The “Essequibo” is a remodeled British River-class minesweeper that Guyana acquired in 2001. As for recent acquisitions, the Guyanese obtained three speedboats in 2014, which were donated by the United States as part of Washington’s Caribbean Basin Security Initiative.

The Guyanese coast guard could hypothetically be a challenge to the Venezuelan Navy, but the latter country’s fleet has also been upgraded and expanded under the Chávez and Maduro regimes. For example, Venezuela has acquired Stan Patrol vessels for its coast guard as well as transport and multipurpose ships from Damen Shipyards Group. The Venezuelan Navy is also repairing its submarine fleet, as the submarine “Sabalo” is currently being upgraded by the DIANCA shipyard in Puerto Cabello.

Given this major disparity in military might, it would be next to impossible for Venezuela to not appear as the aggressor should a maritime conflict occur.

Why Countries Do Not Go To War

If anyone thought in 1899 that the agreement would solve the territorial dispute between Venezuela and the UK/Guyana, that person was grossly mistaken. While the dispute has thankfully remained non-violent, there have been a series of small incidents and diplomatic spats within the past decade. While the probability of either government committing itself to an armed conflict is very low, it would only take one small incident—i.e. a Venezuelan warship facing off with a Guyanese coast guard ship as the latter protects oil research vessels in the disputed territory—for the encounter to escalate.

This brings up the question of why both nations have not gone to war with each other over the disputed territory, particularly since Guyana gained independence from London in the 1960s and remains significantly weaker militarily when compared to Caracas. In a 2011 essay for Small Wars & Insurgencies, I discussed the lack of inter-state conflict in South America, including the Venezuela-Guyana dispute after the 2007 incident. In the analysis, I state that the last inter-state war in the region occurred in 1995 between Peru and Ecuador, while the last war that had a maritime theater of operations was between Argentina and the United Kingdom over the Falklands/Malvinas in 1982. In other words, while there are plenty of territorial disputes in Latin America, actual inter-state warfare is scarce.

What explains the absence of war between Venezuela and Guyana, as there have been three incidents in less than a decade but no shots fired (though a couple of explosions over the dredges)? In spite of the territorial and maritime claims, the two countries have maintained good diplomatic relations as Guyana is a member of Venezuela’s PETROCARIBE initiative. It is nevertheless concerning that Venezuela has called in its ambassador to Guyana and cancelled negotiations over Guyanese rice as good trade relations are an important confidence building mechanism that serves to counterbalance security concerns. The deal will only expire in November, so there is a chance that Caracas is using the deal to temporarily punish Georgetown over the maritime dispute but will renew negotiations later. If this does not happen, it will force Guyana to look for other trading partners for its goods elsewhere, further creating a breach between the two governments and populations.

Moreover, the 2013 and 2015 incidents can be interpreted not as threats to Guyana but rather as methods that the Venezuelan government and Navy used to demonstrate that they maintain their claim to the territories in dispute, seeing this is part of Venezuelan national identity. The same can be said for the new presidential decree 1.859, which does mention specific coordinates for Venezuela’s maritime claims – this way the Venezuelan government does not appear aggressive as it is not implying that its naval forces can now enter Guyanese-controlled waters.

As to whether there was ever a time when Caracas was realistically willing to start an armed conflict with Guyana in the past decade, I would say no. I would argue, as previously noted, that these incidents occurred because the Venezuelan government, Navy, and Army wanted to show that they continue to see Guyanese territory as rightfully belonging to Caracas. Moreover, the quick support that Guyana received from its CARICOM allies, who are also PETROCARIBE clients and even ALBA members, signaled to Caracas that further aggressive initiatives would hurt its relations with its allies; hence, the latest conflict has been short-lived.

Finally, it is necessary to discuss how Venezuela perceives its geopolitical situation versus potential (or imaginary) adversaries. After all, Colombia remains a steadfast U.S. ally. Meanwhile Brazil maintains cordial relations (including security-related) with Venezuela, but the two are in competition with each other for regional influence. Hence, policymakers in Caracas may perceive closer Washington-Georgetown relations as the U.S. and its allies encroaching on Venezuela.

I cannot speculate whether anyone in the Venezuelan military or Ministry of Defense truly believes that Washington would come to Georgetown’s aid if it is attacked, but the fact that the U.S. military has increased its cooperation with Guyana, including training exercises, has certainly not gone unnoticed. Nevertheless, even with some U.S. defense support, Guyana remains a militarily weak state, and Venezuela would undoubtedly be regarded as the aggressor in any military conflict between the two. In a vastly interconnected world, Venezuela’s international reputation would be significantly damaged if it were viewed as an aggressor. Hence, the potential for international shaming can also serve as another deterrent to avoid conflict (a country like Russia may see little problem with gaining this “label,” but Venezuela is no global power).

Ultimately, the interception of the Teknik Perdana or the ongoing dispute after the Exxon discovery are ways for Venezuela to flex its diplomatic and military muscle, not just at Guyana (to demonstrate that it still claims the disputed territory) but also at Washington. Just this past March, President Maduro ordered new military exercises in order to demonstrate his country’s military might. This came at a time when Washington had declared Caracas a “national security threat.”

Guessing the Future

The possibility for an inter-state conflict between the two countries, even over oil, remains low. Nevertheless, what is problematic is the potential for a small incident to quickly evolve into a greater one. For example, should a Venezuelan vessel, let us say the patrol vessel “Guaiqueri” (PO-11), detain an Exxon research vessel, the Guyanese “GDFS Essequibo” could then be deployed to assist the Exxon vessel. As a result, a standoff could occur where, unless cool heads prevail, any action taken by one vessel could be perceived as an aggressive move by the other. This escalation is not unheard of in the region. In 2008, a Colombian military operation that was carried out against FARC insurgents in Ecuador (without Quito’s approval) increased to the point that Venezuela, then ruled by President Chávez, was on the verge of declaring war on Colombia in order to protect the sovereignty of Ecuador, its ally.

Thankfully, the current tensions over Exxon’s oil explorations appear to be dissipating, but it is just a matter of time before another incident occurs, particularly if Guyana is fully committed to exploiting its offshore oil and Venezuela continues to claim the area. I would argue that another round of maritime incidents will occur soon given the creation of the aforementioned “ZODIMAIN Atlantica.”

Warfare may not come to the Venezuela-Guyana border, but it is clear that inter-state disputes among Western Hemisphere states over territory and resources will not end anytime soon.

W. Alejandro Sanchez Nieto is a Senior Research Fellow at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs where he focuses on geopolitics, military and cyber security issues in the Western Hemisphere. He regularly appears in different media outlets like the Toronto Star, Opera Mundi, Russia Today, Al Jazeera, BBC, Le Figaro, El Comercio (Peru) among others. His personal blog is: “Geopolitics” (http://wasanchez.blogspot.com/ ) and his Twitter handle is @W_Alex_Sanchez.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.