This article was originally published by the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) on 1 December 2016.

President-elect Trump’s book The Art of the Deal applies the principles of negotiation to business, but they are universal to human nature. A century ago, a previous president indicated similar sentiment when Theodore Roosevelt wrote “Speak softly and carry a big stick.” Latent power fuels deals. Upon entering the highest office in the land, President-elect Trump will engage in entirely new types of negotiations. And in this new venue, military power is the new trump card.

U.S. military strength gives the United States leverage in the global arena.

Military power is not organic or constant. It requires investment, innovation, and maintenance. Deploying military power degrades it and requires later revitalization. Adversaries adapt to the most advanced equipment and effective tactics. New threats emerge while old ones wane. Military leverage stems from warfighting advantage, which encompasses two simultaneous requirements: the ability to project military power abroad and to protect the U.S. homeland.

Unfortunately, the ability of the United States to do both missions has diminished. The Budget Control Act (BCA) instituted severe defense spending cuts that have harmed military readiness and delayed needed modernization. Additionally, advanced weaponry and high-tech innovations among potential adversaries have hurt America’s ability to project power and defend the homeland. The United States no longer holds a monopoly on the most advanced technologies or techniques. Finally, broken and bloated Pentagon processes have hampered innovation, driven up costs, extended timelines, and prevented necessary personnel changes. These problems are significant but not intractable. By increasing funding, adapting military capabilities, and reforming Defense Department processes, President-elect Trump can rebuild the U.S. military, increasing his leverage in international affairs.

1. Increase Funding with Predictable Planning

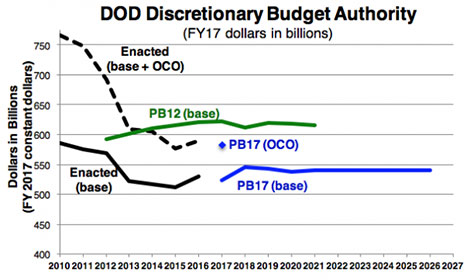

Severe budget cuts have hampered military readiness and modernization. The BCA imposed budget caps approximately $1 trillion lower than the 2012 President’s Budget over the next 10 years. Two subsequent Bipartisan Budget Acts (in 2013 and 2015) increased the caps slightly but extended the duration of mandatory sequestration. Global challenges have not diminished, forcing the Pentagon to do the same with less. This budget has not adequately funded the necessary pilot flying hours, maintenance, and training to keep up military readiness. Critical modernization projects that are needed to ensure the United States can keep pace with potential adversaries have been delayed in the budget-constrained environment.

While short-term budget deals temporarily dodged the budget caps in recent years, they have extended the duration of the BCA caps. These work-arounds provided short-term relief but have not provided the consistency needed for longer-term planning. Acquisition cycles and readiness forecasting require funding stability. Like any business, the Department of Defense (DoD) needs predictable funding to plan needed investments to maintain and advance the U.S. military advantage. To adequately defend the nation, DoD needs significantly more funding. The new administration should seek a budget deal for stable, increased funding at levels above the Fiscal Year 2017 President’s Budget request.

2. Adapt Military Capabilities to Emerging Challenges

Traditional U.S. military capabilities are so effective that adversaries have adapted to avoid U.S. strengths at both the “high” and “low” ends of the spectrum of warfare. The high-end threats emanate from near-peer actors, such as China and Russia, who have built technologically competitive systems that threaten or challenge even the most advanced U.S. weapons and capabilities, including stealth and precision munitions. Collectively sometimes called anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities, these systems can threaten U.S. superiority in domains that have traditionally been assumed secure. For example, U.S. ground forces have not fought without air superiority since the Korean War. New enemy systems such as advanced radars, aircraft, and long-range missiles threaten U.S. overmatch and hamper U.S. power projection. For the United States to continue to project power in the face of these advances, U.S. forces will need to adapt. New investments and concepts of operation are needed.

On the other end of the spectrum, terrorists and insurgents avoid the U.S. advantage in conventional engagements through guerrilla tactics, avoiding decisive engagements with U.S. forces. In recent years, state adversaries have similarly adopted “gray zone” tactics of using military power below the threshold for U.S. responses. While responding to these “lower-end” challenges often does not require expensive cutting-edge technology, it does require deployed assets and personnel, as well as some unique training and equipment for these missions.

The United States must be able to operate across the full range of adversary tactics, which requires increased investments at either end. Even with an expanded budget, the United States cannot afford everything, which is why a “high-low mix” is the preferred option for adapting the force. The United States should increase its investments in resilient power projection for countering A2/AD threats, such as long-range strike and undersea warfare, while also buying low-cost utility platforms to take up responsibility for day-to-day missions. As the force adapts, DoD leaders must be willing to cut less useful assets when necessary to free up resources for future investments.

Even as the United States strengthens its ability to project power abroad, it must shore up its defenses at home. Adversaries’ innovations in both technology and tactics have eroded the natural defensive advantage that America’s oceans provide. Terrorism and weapons of mass destruction continue to pose risks to the United States at home and abroad, albeit at a reduced level than before 9/11. New threats have also emerged. North Korea continues to grow its nuclear arsenal. North Korea, Russia, China, and Iran are developing long-range missiles capable of targeting the U.S. homeland. Cyberattacks are an ongoing threat and can reach across geographic space without warning. Increased access to space is threatening traditional U.S. dominance there as well. These vulnerabilities threaten the U.S. military’s ability to mobilize and project power by putting at risk the military’s global command-and-control architecture. Many of these vulnerabilities also directly threaten U.S. citizens’ physical safety and economic welfare. U.S. leverage is undermined if adversaries can threaten attacks against the United States, and the military must again innovate its capabilities and concepts of operation to strengthen its ability to defend the U.S. homeland.

Emerging technologies will be critical to restoring America’s military advantage. Robotics, autonomy, swarming, electronic warfare, data processing, networking, and advanced munitions are just some of the areas that will shape the future of warfare. The United States has been a leader in military technology, but that advantage is not assured. Continued investment is needed, along with a culture of experimentation to develop the best ways of using new technologies.

3. Reform Department of Defense Processes

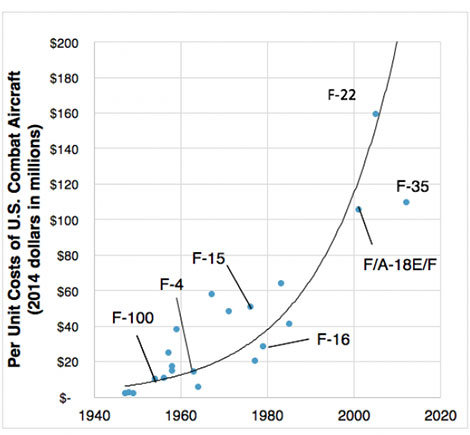

These investments must be coupled with reform of Defense Department processes if DoD is to stay ahead in the continuing cycle of innovation against adversaries. President-elect Trump makes no bones about his intention to reform Washington, and he’ll find ample opportunity at the Pentagon. As a builder, Trump understands how to manage major projects. He is likely to be appalled by what he finds at DoD. The disconnect between the pace of innovation in the commercial and military sectors is astounding. Trump Tower was completed in four years: the ground was broken in 1979 and completed in 1983. Information technology moves forward at a breakneck clip measured in months. By contrast, it takes roughly 15 to 20 years to build major defense systems. In addition to operational risks in delaying fielding equipment, long timelines raise costs, allow for more slippage in requirements, and virtually ensure that equipment will be outdated before it is even fielded. Per unit costs for major platforms such as ships and aircraft have been rising exponentially for decades. To offset rising costs, fewer units are purchased, leading to a steadily shrinking force even in times of budget growth. Combined with A2/AD challenges, this reduced quantity is a perfect storm for military weakness. If the United States is to restore its military advantage, it will need to reform its requirements and capability development processes to innovate faster, control costs, and increase quantities.

Other parts of DoD are similarly ripe for reform. Unnecessary headquarters should be reduced, including consolidating the combatant commands and reducing headcount at the top and the associated staff. “Brass creep,” increasing numbers of senior military officer billets, should be reduced to a more manageable number. This will have trickle-down efficiency gains due to the large size of senior officers’ personal staffs. Additionally, unused or underused military bases should be closed. While base realignment and closure (BRAC) is politically difficult, it is financially necessary. Finally, military compensation and healthcare both need reforms to maintain solvency and competitiveness with civilian counterparts.

President-elect Trump has often said he hires the “best” people, a trend he should continue in DoD. The U.S. military today is the most combat-experienced, professional force the nation has ever seen in peacetime, but it will take continued adaptation of personnel processes to sustain the best personnel. Military careers have historically been limited by rigid career paths and promotion processes, which are now out of step with the broader economy. The promotion system should be reformed to allow for flexible career paths, which would help maintain existing talent. Increasingly, select civilian skills, such as cyber security or key languages, are needed. The military should make it easier to bring civilians with these skills into service. This could include modified physical fitness standards, technical career tracks, and increased flexibility for those who want to move more easily between military and civilian jobs. Finally, demonstrating accountability at the top will keep the best talent in the system and ensure quality standards are maintained throughout the force.

These recommendations are simply a starting point – DoD has many challenges to overcome. While a time of transition introduces many questions, there is also significant opportunity for positive change as new minds consider these challenges and a new president seeks to make his mark. Improving the U.S. military will strengthen President-elect Trump’s hand in negotiations on the world stage and start his presidency with positive momentum toward success.

About the Authors

Paul Scharre is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Future of Warfare Initiative at the Center for a New American Security. Lauren Fish is a Research Associate with the Defense Strategies and Assessments Program and Future of Warfare Initiative at the Center for a New American Security.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit our CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Publications.