Over the last year, a number of top government officials in the United States and Europe have called upon FIFA to punish Russia by moving the 2018 World Cup to another country. FIFA has refused to do so, claiming that the tournament can be “a powerful catalyst for constructive dialogue between people and governments.” This idea is based on the theory that international sports encourage peace and cooperation between countries. FIFA frequently champions this theory as if it is a proven fact, but without providing much evidence to support it.

The World Cup may influence society in many positive ways, such as by encouraging exercise, entertaining the masses, and giving fellow citizens something to bond over. If it also promoted international peace, we would have yet another reason to feel good about investing so much of our time and energy in it. However, there is more evidence that the opposite is true – that international sporting events like the World Cup actually increase the likelihood of conflict.

The World Cup and interstate conflict

Indeed, history provides little evidence that pitting countries against each other in the competitive arena is good for international relations. In fact, a number of examples seem to suggest the opposite. The most famous is the 1969 Football War between El Salvador and Honduras, where football riots between fans escalated into a full-scale war that killed about two thousand people. A more recent example is the 2009 Egypt-Algeria World Cup Dispute, which also started over football riots. The incident caused a heated political conflict between the two countries that resulted in Mubarak pulling his ambassador from Algiers. Another recent case occurred last October, when Albania and Serbia found themselves in a football dispute over a fight between fans and players that erupted when a drone carrying the Albania flag flew into a football stadium and landed on the field during a game.

Cases like these have led many scholars, including George Orwell and Christopher Hitchens, to conclude that international sports increase conflict between countries by inciting nationalism. Particular attention has been given to how dictators often use sports to increase their legitimacy and occasionally rally support for aggressive foreign policies. Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin were all famous for generating nationalism through sports. The most notable example is the 1936 Nazi Olympics, which Hitler used to provoke feelings of Arian supremacy and victimization in Germany during the lead-up to World War II. This tendency of non-democracies to use sports to generate nationalism has reoccurred throughout history, with the 2008 Beijing Olympics being one of the most recent examples.

The link between international sports and conflict is also supported by statistical analysis that tests how international sports influence state aggression. The ideal way to tackle this question would be to run an experiment where a large number of countries are randomly selected to attend a major international sporting event and others randomly chosen to stay home. The aggression levels of the treatment and control groups before and after the sporting event could then be tracked, in much the same way as medical researchers test the effect of a drug through a randomized controlled trial. These experiments are the gold standard for establishing causal relationships in most scientific fields, so the results from this type of study could significantly improve our understanding of how sporting events affect interstate conflict.

Although there has never been a real experiment that tests how sports influence state aggression, the format of the World Cup qualification process from 1958-2010 created a natural experiment that is very similar to the ideal study described above. Over this period, many countries qualified for the World Cup by playing a round of games against other teams and earning a top position in the standings. It is therefore possible to compare the group of countries that barely qualified to the group that just fell short. The idea is that if Switzerland scored 15 points in the standings and qualified, while Portugal scored 14 points in the standings and missed out, then it is basically a coin flip which of these countries went to the World Cup.

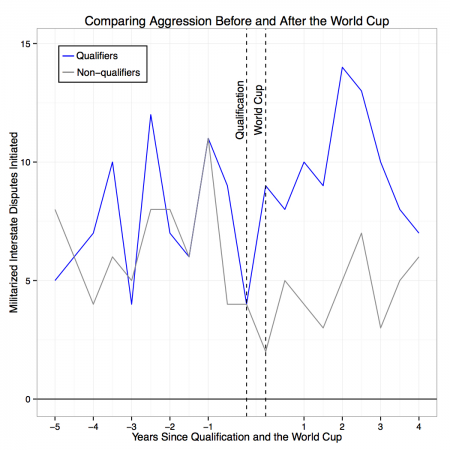

After researching the entire history of the World Cup, there were 142 countries that barely made or barely missed qualification. The qualifier and non-qualifier groups are very similar across many military, economic, and demographic factors, including past levels of aggression. Aggression can be measured using the number of Militarized Interstate Disputes that each country initiated, which is the standard measure of state aggression in political science. These disputes are cases where states explicitly threaten, display, or use force against other countries. This measure is commonly used in security studies, since full-scale wars happen too rarely to be a useful measure in most statistical tests.

The results provide strong evidence that the World Cup increases international conflict. As the graph below shows, the qualifiers experienced a large spike in military aggression during the World Cup year. The difference in the aggression levels of the two groups is statistically significant at the 1% level. In fact, if the World Cup did not really tend to make countries more aggressive, the probability of seeing a divergence this large by chance is less than one in 150.

The estimated treatment effect is also much larger for two types of countries. The first is countries where football is the most popular sport. In fact, countries like the United States where football is not the most popular sport experienced no change in aggression after going to the World Cup. The second is non-democracies. While democracies appear to become somewhat more aggressive because of the World Cup, the effect appears to be about 50% larger for non-democracies. This finding is consistent with past historical research on the strong relationship between sports and nationalism in authoritarian countries.

The next football war?

These results suggest the 2018 World Cup in Russia will probably do more to intensify the dangerous political situation than to resolve it. Putin will likely use the event to incite nationalism, much like he did during the 2014 Sochi Olympics that took place just days before Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine. While the World Cup has many positive effects, it simply does not appear to be very good at encouraging peace between countries. Thus, FIFA should choose its policies wisely if it wants to help reduce international conflict through football. Believing that the World Cup always fosters peace could have very dangerous consequences.

Andrew Bertoli is a PhD Candidate in Political Science at UC Berkeley. His research investigates how national unity affects interstate conflict. He uses natural experiments to show that social and institutional unity at the domestic level can increase conflict at the international level.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.