Image courtesy of Guillaume Périgois/Unsplash.

This blog belongs to the CSS’ coronavirus blog series, which forms a part of the center’s analysis of the security policy implications of the coronavirus crisis. See the CSS special theme page on the coronavirus for more.

The EU as a foreign policy and security actor is often haunted by the “capabilities-expectation gap”, referring to the discrepancy between the expectations citizens and states have about the EU’s international role and what the EU is actually able to deliver. The gap consists of three main components: available instruments, resources, and the ability to agree.

The 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) will go down in history as the EU’s coronavirus budget – unprecedented in volume and the raising of joint debt. It features several new defense initiatives complementing the EU’s long-standing efforts to narrow the capabilities-expectations gap. While the budget places promising new instruments at the EU’s disposal, the trimming of resources initially allocated and unchanged decision-making procedures significantly dim the prospects for those initiatives to deliver the expected results. If these projects are to bear fruit, they must be prioritized and interlinked with existing programs and supported by strong financial commitments by the member states.

A new trio of instruments

The future MFF introduces three new instruments available to the EU in the domain of defense, beginning with the European Defence Fund (EDF). The EDF, described by some as a “paradigm shift” for what arguably used to be primarily a “civilian power”, will enable the EU to invest directly in military technologies. The shift must be seen against the background of rising armament costs, declining European defense budgets, and a lack of cross-border collaboration, as manifested in the limited interoperability and duplication of military systems within the EU.

By providing co-funding dedicated to collaborative defense projects in their research and development (R&D) phase, the fund is intended to boost the competitiveness of Europe’s defense industrial base, strengthen its technological sector, and increase member states’ military capabilities.

The second instrument relates to the “practical art of moving armies” across member states’ borders. In the EU, such troop movements are still hampered by several physical, procedural, and regulatory obstacles. This strategic vulnerability became apparent after Russia’s revanchist actions in eastern Ukraine, starting in 2014, and prompted the EU Action Plan on Military Mobility.

The program aims at further developing Europe’s dual-use infrastructure as well as simplifying diplomatic clearances and customs procedures to speed up troop deployments on EU territories. Unofficially referred to as “military Schengen”, the initiative is a response to security concerns raised by Eastern European states and NATO.

The final instrument is the European Peace Facility (EPF), a permanent fund running alongside the EU budget but financed by member states’ contributions, designed to cover common military operations of EU member states. By harmonizing pre-existing mechanisms, namely the Athena mechanism and the African Peace Facility (APF), the EPF addresses their gaps and significantly expands the EU’s capabilities to engage in military assistance. Unlike Athena, EPF funding will be permanently available and therefore more predictable, absorb a higher share of total operation costs, and cover a broader scope of activities.

In contrast to the APF, the EU can provide military capacity-building, including lethal support, directly to armed forces led not only by regional organizations, but also by third states and international organizations. Geographically, the EPF is no longer bound to operations on the African continent, but can be used globally.

More resources and yet too little

It is a symbolic novelty in the EU budget’s history that spending on security and defense is featured in a separate heading. Financially, this formal change is reflected in new funds flowing into both new and older projects.

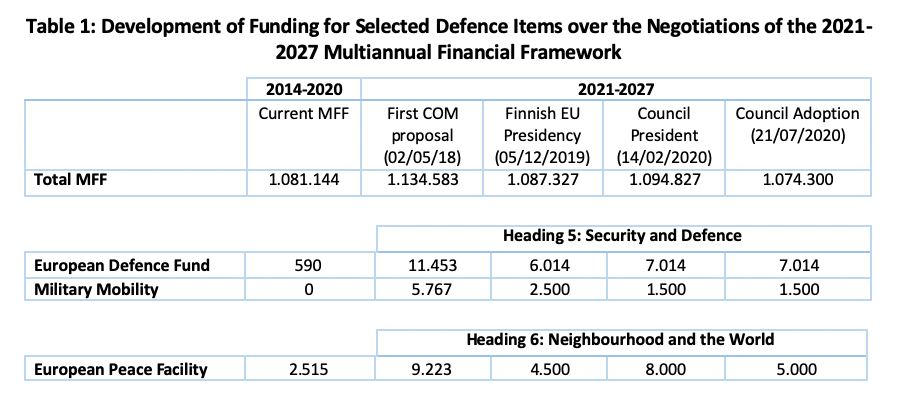

However, in view of the initial proposal presented by the European Commission, overall defense spending has been watered down drastically (see Table 1). The 2019 Finnish Council presidency proposal envisaged more cuts to defense than to any other budget line. This set the bar very low for future negotiations and, once the coronavirus crisis broke out, raised fears amongst some defense ministers that the planned initiatives could be left out altogether.

Ultimately, these fears were unfounded, as were the hopes of those who saw the COVID-19 crisis as a potential boost to European defense. The appetite for higher defense spending was already low before the outbreak of the virus, but wasn’t much affected by savings pressures imposed by the pandemic either.

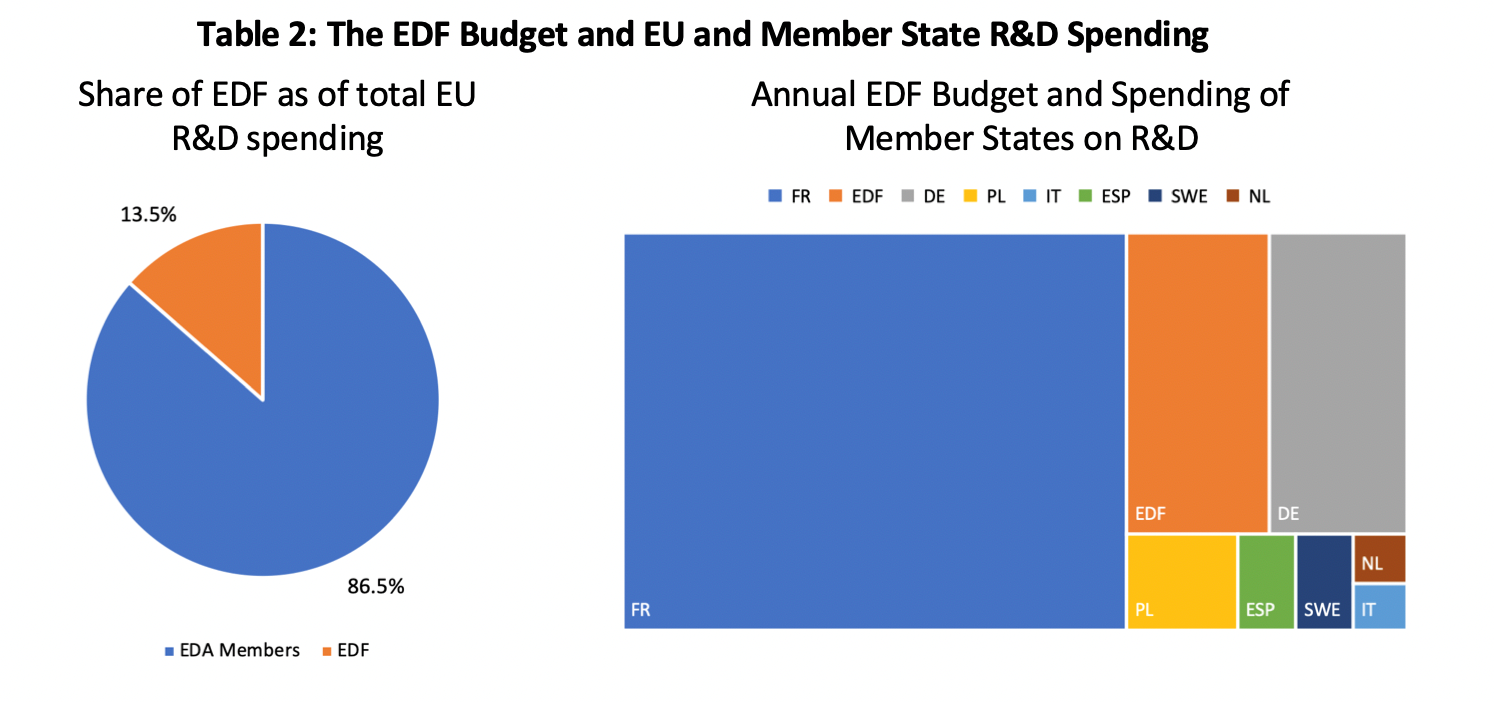

Standing on their own, these numbers are abstract. The magnitude of the EDF is easiest to assess when compared to the R&D spending of member states (see Table 2). At roughly €1 billion a year, the EDF is comparable to Germany’s annual R&D expenditure and will represent 13.5 per cent of the EU’s total.

The final size of the military mobility envelope, which was reduced by nearly a quarter, will hardly suffice to close the identified gaps in dual-use infrastructure. Moreover, since all three instruments are matched by national contributions, a reduction of funding from the MFF automatically reduces the amounts flowing from member states, further shrinking the initiatives’ total size.

Note: Numbers in millions of Euros in constant 2018 prices. The European Peace Facility in the 2014-2020 MFF is the sum of the African Peace Facility (€2.085 million) and the Athena Mechanism (€430 million for 2014-2019). Source: For the AFP, see the Action Programmes 2014-2016, 2017-2018, and 2019-2020. For the Athena mechanism, see figures for 2014 and 2015-2018. For 2019, numbers were provided by the General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union.

Note: Total EU R&D spending excluding Denmark and the UK. Data for the year 2018. Source: European Defence Agency Defence Data Portal.

Unaltered decision-making processes

A change in budget is not a change in the treaty, no matter how historic and far-reaching the changes in the former are. While the issuing of common EU debt lays the foundational work for a fiscal union and thus marks a profound integration step, none of the afore-mentioned instruments will significantly alter the EU’s (in)ability to agree on matters of common security.

In case of the EPF, the higher sharing of common operational costs and widened competencies notwithstanding, member states must still decide on proposals for common action on the basis of unanimity and ultimately generate forces.

The only instrument introducing changes to the inter-institutional balance, adding a dose of supranationalism, is the EDF. The European Commission, which had previously not been involved in the defense field, emerges as a new political actor equipped with €7 billion to allocate to the European military-industrial complex. This will lend the Commission considerable agenda-setting power and creates opportunities to push for a more European approach, but raises new questions over the EDF’s democratic accountability.

Narrowing or widening the gap?

In the realm of defense, the new MFF creates a familiar dilemma for the EU, namely that the announcement of new, auspicious initiatives that expand the EU’s formal capabilities ultimately also raises expectations the EU may not be able to meet.

The reluctance to back those instruments with substantial resources and the prevalence of unanimity rule weakens their potential to bridge the EU’s underlying structural differences: Concerns over sovereignty, different strategic cultures, and fragmented defense markets continue to impede a full-fledged European defense cooperation. Therefore, a range of other factors are required for the new instruments to bring any tangible improvements.

It will be necessary to prioritize a few key projects. For the EDF, this means focusing on projects of highest strategic importance and economic viability. The same applies to military mobility, where investments to improve the railway infrastructure in Eastern Europe would complement NATO’s rapid-reinforcement strategy towards Russia.

Using synergies, maintaining coherence, and synchronizing new EU initiatives with pre-existing ones will be pivotal too. PESCO, for example, has already brought forward a range of advanced projects the EDF could build on.

Lastly, member states should engage constructively with and provide additional funding for the initiatives, despite budget pressures. Although it can be argued that reduced budgets incentivize member states to draw on EU funds and invest more cost-efficiently, the outlook is tarnished, as the economic fallout of the coronavirus crisis provides new arguments for protecting national industries and the jobs related to them.

The new MFF is at the heart of the EU’s bold financial and integrative answer to the COVID-19 crisis. However, as in other policy domains, defense integration is not an end in itself, but must add concrete value for Europe’s security architecture. Otherwise, the gap between the EU’s capabilities and the expectations will only widen, much to the detriment of the EU’s credibility as an international actor.

About the author

Marc Friedli is an intern in the Swiss and Euro-Atlantic Security Team at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.

One reply on “The New EU Budget and Defense: Narrowing the Capabilities-Expectations Gap”

Great article!