This article was originally published by Geopolitical Futures (GPF) in February 2018.

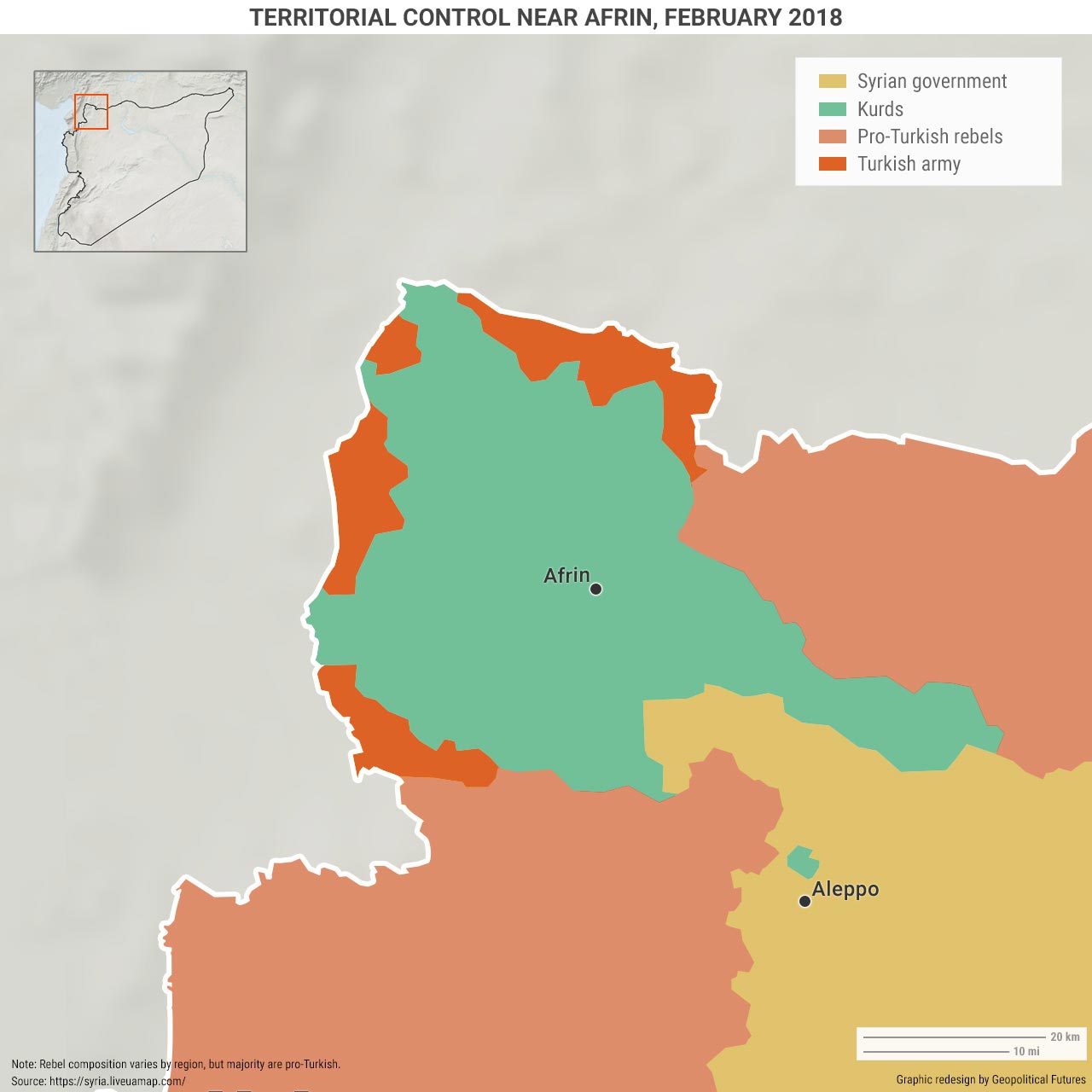

The nature of the conflict in Syria is changing shape again, with two important developments taking place over the past week. First, Turkey proposed cooperation with the United States in Afrin and Manbij, both of which are held by Syrian Kurds, whom the Turks consider hostile forces. Though no formal agreement has been reached, U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis said the U.S. would work with Turkey to coordinate their actions in Syria. Second, the Syrian Kurds appear to be willing to work with the Syrian regime against the Turkish assault on Afrin. Pro-regime forces reportedly entered Afrin on Feb. 20, a move that would require coordination with the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, or YPG, which controls the region.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has downplayed Turkey’s involvement in Afrin, pitching the invasion as both a necessary and low-cost military operation. But the involvement of pro-regime forces changes what will be required of Turkey to take control of the region. So far, Turkey has used a minimal number of its own forces in Afrin and mostly relied on the Free Syrian Army and other anti-Assad groups. But with pro-Assad forces now taking part in the conflict, Turkey will need to do more if it wants a successful outcome.

Turkey’s Breaking Point

Turkey will have to consider how much blood the Turkish people are willing to shed to take Afrin and the northern corridor in Syria that extends from the border to the Euphrates. It’s hard to know what the breaking point is for the Turks, but we can look to Turkey’s last major military intervention for clues. In its invasion of Cyprus in 1974, Turkey incurred roughly 570 combat deaths. With a total force of 60,000, that is a 1 percent fatality rate for a monthlong operation that secured Turkey’s control of a substantial portion of the island.

Turkey recently said approximately 30 Turkish soldiers have been killed in the monthlong operation in Syria, though this number may be understated. In late January, Haberturk, a Turkish news agency, said 6,400 Turkish soldiers would take part in Operation Olive Branch. Other sources, however, report that Turkey has upward of 15,000-20,000 troops deployed at the Afrin border. (There are also 25,000-30,000 Free Syrian Army militants acting as Turkey’s proxies in Syria.) If the official fatality numbers are to be believed, the Turkish army has incurred a death rate of 0.15 percent to 0.47 percent, well under the death rate in the Cyprus operation, which did not face widespread public backlash. The difference between Cyprus and Afrin, however, is that after a month in Afrin, Turkey doesn’t seem close to securing its military objective.

Syria, the Kurds and a Possible Settlement

Bashar Assad’s goal in Syria now is to regain control of as much territory as possible. With Turkey joining the fray in Afrin and inching closer to Aleppo, a critical city over which Syrian forces have already fought a bloody battle, Assad has a choice: either escalate his military conflict with Turkey and its proxies, or come to a settlement. To win a military victory in the region, Assad would need to move his forces along the southern edge of Afrin until they reach the Turkish border in the west and then turn farther south until pro-Turkish forces in Idlib – a region largely controlled by another Turkish proxy, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham – are surrounded. Assad will try to encircle Turkish proxies in Idlib and cut off their supply routes to Turkey.

From the regime’s perspective, therefore, working with the Kurds makes sense. It can use the 8,000-10,000 YPG fighters in Afrin to repel the Turkish invasion and avoid expending its own resources. It also makes sense for the Kurds, who are facing a Turkish assault with few allies, since the U.S. has said it will not support the YPG in Afrin.

But Turkey also has plans to surround the YPG and cut off access to its allies. On Feb. 20, Erdogan announced that the Turkish military will in the next several days attempt to envelop Afrin, blocking the YPG from receiving support from pro-Assad forces. Turkey and Assad are therefore applying the same strategy to different regions, while trying to avoid a confrontation that could draw in more outside powers and escalate the conflict.

This situation could give rise to a tactical settlement in Afrin. Faced with the risk of a far bloodier battle than it anticipated, Turkey may be willing to halt its advance if the Syrian regime – and by extension, Iran and Russia – agrees to move the Kurds out of Afrin and Manbij to an area east of the Euphrates, and if it could also guarantee to control the Kurds’ actions thereafter. The Syrian government could then take control of areas that have been held by semi-autonomous Kurdish entities for several years. The Syrian Kurds might also agree to this arrangement – it would allow them to avoid even more bloodshed, and they could negotiate a role for themselves in the Syrian government. Iran, an Assad ally, might also accept an agreement because it would reverse Turkey’s advance east. Such a settlement wouldn’t end the Syrian war, but it would help temper the conflict in Afrin.

The success of this type of settlement depends on whether Turkey would be satisfied with an agreement to relocate the Kurds. If Turkey’s ultimate goal in Operation Olive Branch is to secure greater strategic depth – and we believe it is – rather than to simply clear the YPG presence in Afrin as Ankara claims, then such a settlement will be a harder pill to swallow. But the Turkish public may not tolerate a sustained, costly military operation in Syria. If Turkey does agree to a settlement, it is safe to conclude that Turkey’s rise as a regional power will be accompanied by some setbacks.

Russia and Iran Compete for Control

For its part, Russia wants a settlement that would leave Assad strong and willing to follow Russia’s – not Iran’s – lead. This might involve Assad regaining control of Afrin. Russian President Vladimir Putin would get to declare victory and get Russian forces out before too many more get killed. Russia has already made one proposal that involved the handover of Afrin to Damascus, although it was rejected by the Kurds.

But Russia has also signaled that it is willing to allow a Turkish presence in Afrin. Putin was willing to work with Turkey during Operation Olive Branch, allowing it access to Afrin’s airspace. Erdogan also said he spoke to Putin on Feb. 19 and convinced him to prevent the Syrian army from deploying to the region. (So far, only pro-regime militants have reportedly been deployed.) It appears for now that Putin will let the regime fight back against Turkey – but within limits. After all, if a large portion of the Syrian army were to be redeployed, Russia would have to contribute more resources to the offensive in Idlib.

Russia can accept the Turkish presence in Afrin because Russia stands to benefit from the heightening competition between two regional powers that are on opposite sides of the Syrian war: Turkey and Iran. Russia has been tactically cooperating with both, but ultimately it wants neither to emerge from the war in an overwhelmingly powerful position. Right now, Iran has the strongest position in the Middle East, able to wield power in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. Russia and Iran both support Assad, but Moscow doesn’t want Tehran to be able to challenge Russian interests either in the Middle East or in the Caucasus.

Luckily for Russia, it can wait longer than Iran can. Every move Turkey makes eastward brings it closer to a confrontation with Iran in Iraq. So long as Turkey and Iran are fighting each other (or each other’s proxies) and stay south of the Greater Caucasus mountain range, Russia can afford to be minimally involved.

Russia and Iran are effectively playing a game of chicken. Russia knows that Iran cannot afford to have Turkey seriously challenge Assad by taking Afrin and thereby surrounding Aleppo. This will force Iran to spend more blood and treasure on halting the advance in Syria, placing further pressure on Iran’s already strained resources. Russia, meanwhile, can continue to provide minimal air support in Syria. Short of a settlement on Afrin between Syria, the YPG and Turkey, Iran will be forced to commit an ever-increasing number of troops and resources to Syria as Turkey conquers new territory.

Testing U.S.-Turkish Relations

The deployment of pro-regime forces to Afrin complicates Turkey’s proposal to work with the U.S. in Afrin and Manbij. Iran’s rising power has brought U.S. and Turkish interests closer together, despite the United States’ longstanding support for the Kurds. The U.S. now has to decide what’s more important: containing Iran, or supporting the Kurds. While this dynamic plays out, the Islamic State remains a threat, leaving the U.S. looking for allies on the ground willing to fight IS.

Underlying all this is a bigger question: What would Russia do if the U.S. were to engage Assad in a large, more protracted fight? With the Syrian government intervening in Afrin, U.S. cooperation with Turkey could bring Washington into direct conflict with Assad. The U.S. is loath to become bogged down in another war in the Middle East and will encourage Turkey to come to an agreement with Assad that lets the U.S. maintain a minimal force there to fight IS. If Turkey wants to press its advantage, rather than suffer what it may perceive as a setback, it will be yet another test of U.S.-Turkish relations.

About the Author

Xander Snyder is an analyst at Geopolitical Futures.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.