The Haiti earthquake has become the new measure of generosity.

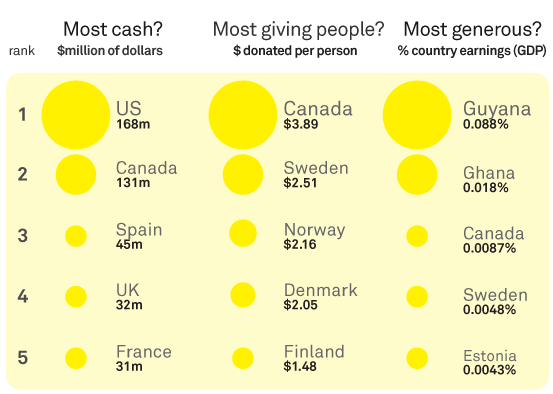

The country’s big northern neighbours have earned much praise for their effort: The US has pledged $168 million to date, and Canada $131 million. The bronze medal goes to Spain, with ‘only’ $45 million, although the latest data from ReliefWeb indicates that Saudi Arabia has caught up.

But data journalist David McCandless puts things into perspective: Measured as a percentage of GDP, the most generous countries in the Haiti crisis have been… Guyana and Ghana! Canada and all Nordic countries make it to the top ten in this wealth-corrected ranking as well, but not Uncle Sam.

Beyond its primary purpose of disaster relief, the donation campaign has lifted Haiti out of the realm of forgotten poverty-stricken nations. This is a chance for the country, but I am worried about two potential pitfalls.

Firstly, such spectacular catastrophes tend to cause unhealthy fads on the charity market. Aid organizations are in a very competitive business: most of them have to fight hard for every dollar they receive and are vulnerable to media-induced donation trends.

As a result, charities that focus on problems that are immediately understandable and easy to portray in the media will have less difficulties securing funding. Those that focus on important ground work, but with few quantifiable results, have a harder time finding money.

If it diverts funds away from other, less publicized development projects, Haiti will be creating other potential Haitis. Natural catastrophes happen everywhere, and the more a region’s institutions and infrastructure are developed, the better equipped it is to face such emergencies.

Aid professionals are well aware that a balance has to be struck between short-term crisis relief and long-term development aid. So be generous with Haiti, but don’t forget the importance of aid that targets places and problems you weren’t aware of: chances are they will be next in the news.

My other worry has to do with the hype that media-friendly humanitarian emergencies cause in the aid community.

The many aid organizations that flocked to the country after the earthquake are there to stay and will indeed be needed for the long-term reconstruction efforts to come. However, significant concentrations of aid organizations make coordination of aid work, as well as the management of adverse effects, very complex.

One of the worst examples of a humanitarian hype has been Kabul since 2001: the presence of aid organizations has driven rents through the roof and encouraged corruption in the housing sector, among other things. The very people that those aid organizations were there to help were further impoverished by rising costs of living.

Increasingly, aid workers integrate the ‘do no harm’ principle into their strategies. Let’s hope it won’t be forgotten in the reconstruction effort in Haiti.

Generosity is a quality to be cherished, but beware: meaning well doesn’t always translate into doing good.

One reply on “Haiti and the Meaning of Generosity”

Foreign Policy picked up on the issue of humanitarian hype just a day later http://thecable.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2010/02/12/haiti_causing_steep_funding_cuts_aid_groups_warn