This article was originally published by the Harvard International Review on 15 April 2016.

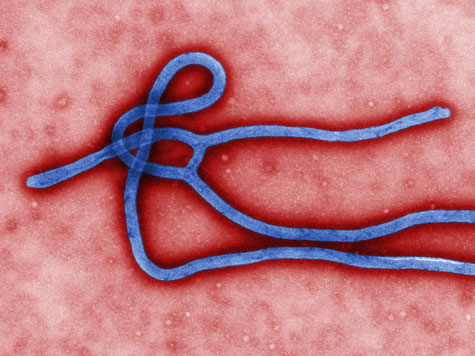

On the heels of the annual International Monetary Fund/World Bank conference and an Ebola-ridden year, the world is reminded of the significance of global health policy, not only for disease prevention but also for international relationships and the future direction of health care. Recent international health initiatives have pragmatically stressed the importance of defense and economics. This slant, particularly in the relatively new Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA), raises questions about future approaches to global health. The GHSA has acquired significant funding for outbreak response, but its treatment of global health as an international security issue rather than a humanitarian one warrants a cautious assessment.

In February 2014, in the midst of the Ebola crisis, the United States unveiled the Global Health Security Agenda. The 30-nation effort promotes “global health security as an international security priority.” Its broad goals are to strengthen countries’ ability to prevent, detect, and respond to health threats. With its US investment of US$1 billion and a collaborative, multilateral spirit, the program is ambitious and potentially far-reaching.

An initiative like the Global Health Security Agenda is crucial for several reasons. Outbreaks of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), H1N1, and HIV/AIDS over the past few decades might have been significantly less deadly with the transparent communication and personnel deployment for which the GHSA calls. A more urgent multilateral response to Ebola likely would have saved countless lives. And an emphasis on security as the top priority could have been effective in calming the widespread panic that accompanied each epidemic.

The GHSA is one of the most clearly security-oriented health initiatives to date. However, over the past decade, global health has played an increasingly significant role in the security policies of countries like the United States and the United Kingdom. In 1998, the US national security strategy hardly touched upon global health. HIV/AIDS received only one mention; public health was characterized as secondary to issues like bioterrorism and environmental degradation. In contrast, in the 2002 US National Security Strategy Report, disease, along with war and poverty, is described as threatening “both a core value of the United States – preserving human dignity – and our strategic priority – combating global terror.” Here, global health goals are equated with the national security agenda. Additionally, the authors argue that global health issues should be solved in order to increase stability, not necessarily to reduce the worldwide suffering stemming from disease and lack of access to care. In the years since the publication of this report, the focus on health as a security issue has further increased. The GHSA embodies the growing influence of this approach.

The United Kingdom placed a somewhat weaker emphasis on health than the United States at the time of the National Security Strategy Report. Instead, it focused on terrorism and weapons of mass destruction as the most pressing threats to national security. However, in a 2003 security plan with a decade-long scope, British leaders still framed health as an important underlying stability issue. The report asserts that success in the fight against terrorism will require action on a number of fronts, including poverty and disease. The plan cites the ability of disease to undermine economic growth and stability, and, by extension, peace.

British officials’ emphasis on health has grown since the publication of this security plan. A 2010 national security plan, for example, places “a major accident or natural hazard” in the top tier of international security threats. One of the subsets of this category is a pandemic, which the authors of the report argue can lead to “significant and wider social and economic damage and disruption.” Much like the US, the UK now approaches global health as crucial because of its implications for international and domestic safety. Just as in the US security report, the UK report does not mention the implications of healthcare for the well being of individuals. The approach taken by the US and the UK is crystallized in the goals and mechanisms of the Global Health Security Agenda.

While introducing the GHSA, Katherine Sebelius, the US Health and Human Services Secretary, said, “A threat anywhere is indeed a threat everywhere.” A White House press release in late July asserted that the United States “will not lose sight of the goal: accelerating progress towards a world safe and secure from infectious disease threats through building our collective capacity to prevent and control outbreaks whenever and wherever they occur.” The Elizabeth R. Griffin Research Foundation, a partner to the GHSA, further articulated aims to “deploy” diagnostics and non-medical measures.

These statements have significant implications. Secretary Sebelius immediately established the GHSA as a defense initiative, and the language of safety and control that the United States employs has militaristic connotations, in contrast to the frequently compassionate characterizations of the medical field. This rhetoric suggests a greater focus on protecting outside countries from an epidemic than on solving it in its nation of origin. The GHSA frames future outbreaks as threatening not because of their potential to infect and kill individuals, but because of their ability to cross borders. As such, an epidemic must be treated like an army of human invaders – with central intelligence, assertion of power, and countermovement.

A major motivating factor for global health initiatives like the GHSA is the potential of disease to reach far beyond somatic damage. Its consequences can extend to political unrest, which can quickly grow into an international threat. Additionally, in arguing for the program, the White House emphasized the detrimental effects of disease on economic vitality; failing economies in turn can lead to greater precariousness. Viewing global health through this lens makes the benefits of investing in the GHSA to the US clear. By committing resources to the reduction of epidemics, US officials can attempt to ensure the strength of economic partnerships and the political landscape, thereby protecting the country’s prosperity and international position.

Furthermore, the GHSA’s emphasis on biosurveillance and its ties to the United States Department of Defense and Department of State allows the US government to assert its influence in countries aided by the initiative. The importance of programs like the GHSA for general safety cannot be discounted. However, as the world moves forward, recovering from Ebola and attempting to prevent other catastrophes, we must be cautious about the balance between security and humanitarianism.

The GHSA stands in contrast to actions like the establishment of UNICEF’s Sustainable Development Goals. The SDGs focus mainly on the welfare of children, aiming to promote access to essentials such as clean water and education and reducing preventable childhood death. While the accomplishment of these goals would clearly be beneficial in terms of world stability and economic welfare, the SDGs were not established in service of these aims. Instead, they focus on quality of life and access to care for the individual. While the GHSA is certainly meant to fill a different niche than the SDGs in global healthcare, its total lack of acknowledgement of quality of life reveals an ideological split that could lead to serious future problems.

It is possible that a national security-centric approach to global health could coexist with a humanitarian one. But programs like the GHSA appeal to a natural, pragmatic desire for security and self-benefit, and their benefits to one nation can be proven more easily. Therefore, these types of programs can divert funding and resources from the broader, more idealistic visions of UNICEF and humanitarian non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Development-focused foreign aid, which in theory is meant to be altruistic, is already largely driven by political power dynamics and economic considerations. Applying this type of logic to healthcare, an area currently grounded in the right to be free of disease, can be dangerous.

If national security becomes an even higher priority, there would be little hope for those suffering from non-communicable diseases in poverty-stricken countries. For example, mental and substance-abuse disorders account for a greater percentage of the global burden of disease than any other illness, yet would likely not receive funding from programs like the GHSA. Mental illness is not technically contagious; a major epidemic of depression that could send governments spiraling, for instance, is unlikely to occur. Mental illness causes significant individual suffering, and its impact extends beyond the patient, to their family and community. However, the goals of the GHSA would not justify the direction of resources to improving mental health care and would likely divert already-scarce funds. Other chronic illnesses, while just as detrimental to overall quality of life as contagious disease, would also be underemphasized. Similarly, UNICEF’s efforts to improve the quality of life for children who might never leave their hometown would be pushed aside.

Furthermore, while global health initiatives are arguably already used as diplomatic tools, an explicitly security-based approach would encourage an even greater use of purely political cost-benefit analysis when establishing programs. When global health is treated as a national security issue, leaders will tend to focus on the volatile regions of the world, rather than those with the greatest health burdens. Additionally, the biosurveillance inherent in policies like the GHSA, without an emphasis on helping individuals within a country, could lead to serious international tension. For instance, programs that track patterns in health systems are implemented to detect epidemics before they can spread. These programs are clearly valuable for the health of all. The GHSA portrays them as important because of their benefits to the safety of foreign countries, not because of their potential to save lives in the country of interest. From this angle, biosurveillance appears to be an invasive, self-interested intervention. Political cost-benefit analysis and biosurveillance are logical approaches from the perspective of national security. However, they risk neglecting those who suffer most and unintentionally exacerbating international conflict.

Applying military strategy and hard logic to problems like world health is tempting. The use of surveillance and defensive strategy has been successful in promoting multilateral goals; by stabilizing the international economy, states aim to bring greater prosperity to their constituents and prevent political unrest. These approaches have the potential to significantly benefit global health initiatives. However, when crafting future policy, leaders must be careful not to neglect the humanitarian foundation of health care. Otherwise, they risk losing touch with, and possibly harming, those individuals they initially hoped to serve.

Laura Kanji is a staff writer for the Harvard International Review.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.