This article was originally published by E-IR.info on 1 April 2014.

Visual Politics and North Korea: Seeing is Believing

By: David Shim. London and New York: Routledge, 2014

More often than not, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, commonly known as North Korea, is featured in the media as a secretive, harsh, irrational, and dangerous country, whose leaders are incapable of interacting with the international community, and whose citizens are slowly dying at the ill will of those leaders. Such characterization has been bolstered – and to some extent popularized, especially in North America – by a number of representations of North Korea as the “other,” the “enemy,” and the embodiment of an “axis of evil,” as well as a country that is so alien and strange that its late leader, Kim Jong Il, was featured as a satirical character in the puppet movie Team America a decade ago.

Considering North Korea in a Broad Context

Indeed, since the end of the Cold War, North Korea has oscillated between collapse and brazen behavior, testing missiles and developing nuclear weapons amidst international pressures and sanctions. More recently, a growing number of North Korean citizens have managed to leave the country and share their stories of life in the totalitarian bastion to a public that is becoming more and more interested in the strange remote country. What we know, and especially do not know, about North Korea has also been a central theme investigated in the academic world. There is a growing body of scholarship that has focused on the historical roots of the Korean War and the subsequent Armistice that have left the two Koreas divided and in a constant state of tension (Moon 1996), and what has resulted in an economic crisis precipitated by North Korea’s domestic choices under both Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il (Gills 1992, Mack 1993). A central and recurring theme in Korea-focused scholarship is the concept of crisis, which has resulted in food and energy mismanagement (Smith 1999, Satterwhite 1998, Snyder 1996), as well as North Korea’s pursuit of weapons of mass destruction (Park 2004, Perry 1999) and non-compliance with international regimes (Rozman 2007, Kang 2003, Mack 1993, Moon 2003, Liu 2003). How to interact with such a state has been greatly debated in the literature as well, with some focusing on how to engage North Korea through negotiation (Cha 2003, Downs 1999, Starkey 2000), sanctions and constraints (O’Sullivan 2000, Downs 1999), creating opportunities via multilateral processes (Park 2005, Quinones 2004), by fostering internal changes within North Korea through NGOs (Flake 2003, Smith 1999), or even by considering international intervention and regime change (Bruner 2003).

What to See and What to believe

Most of the media and scholarship activities focusing on North Korea often have a pre-existing understanding of the country as an actor and, as such, most works are colored by a specific lens which can, in some occasions, weaken the reliability and validity of the findings presented. In his book Visual Politics and North Korea: Seeing is Believing, David Shim, an Assistant Professor in the Department of International Relations and International Organization at the University of Groningen whose research focuses on the Korean peninsula and questions of powers and influence, tackles a number of epistemological questions relating to North Korea. In particular, Shim takes a welcome Critical Studies position by considering how the West (largely) uses images of North Korea to construct a particular narrative and, to some extent, securitize a number of issues and justify foreign policy decisions. Shim also addresses important methodological concerns by engaging the reader in a study of how images can “be utilized for a thorough discussion of their relationship to politics and ethics” (p.7).

The book’s interdisciplinary focus is appealing, as it engages with themes that are not often discussed when considering security issues and North Korea, namely because such agendas have been largely dominated by the more traditional security concerns that see Pyongyang as a threat to the international system and as a threat that needs to be addressed (i.e. eliminated). Hence, Shim presents in Chapter 1 a thorough and interesting discussion of International Relations as a discipline that can benefit from a consideration of aesthetics, but with a focus on the “visual of the everyday and their linkages to the international and the political” (p.11). Such topics are vital to consider, as they help to dispel the myth that we do not know much about North Korea because of its closed borders and tight information control. Indeed, Shim rightly stresses the fact that gathering information about North Korea nowadays is far easier than it was in the past, notably because of the rise of global media networks and the fact that an increasing number of foreigners visit North Korea every year, be it for diplomatic, relief, economic, or even touristic pretenses. Because “imagery of North Korea – especially since the 2000s – has become increasingly prevalent, popular, and is nowhere near as rare as is often assumed” (p.39), works such as Shim’s are important and needed. By asking the question of whose images are shown and what purpose might lie behind such expositions, the book presents a valuable contribution to the field of Critical Security Studies and International Relations, even though the study focuses on a narrow field of analysis: namely, mediated understanding of North Korea via photo-essays and the use of satellite imaging to securitize issues.

North Korean Life in Focus

The two central approaches presented in the book, namely “Seeing on the Ground” (p.57) and “Seeing from Above” (p.91), are framed by a relatively short supporting chapter that presents a variety of representations and practices used when considering, looking at, and analyzing North Korea. This perhaps represents a minor shortcoming of the book: overall, the book is clearly academic, and the engagement with the literature presented in various chapters does not necessarily lend itself to a very popular and wide readership. This is, however, the very readership that would need to be warned of the possibility of trivializing North Korea’s reality, and warned of images representing North Korea as being “manipulated” in the very vein that the North Korean regime exercises control over what it allows foreigners to photograph and what it allows its own media to publicize.

The strength of the book rests, however, in a thorough step-by-step analysis of a number of visual sources, each representing a different North Korean reality, and a careful, non-dogmatic reading that does not focus on which representation is closer to the truth. Shim looks, for example, at an award-winning photographic essay published in Foreign Policy entitled “The Land of No Smile” by photographer Tomas van Houtryve. His analysis also considers textual commentary added to the pictures, as well as the ethical dimension of the pictures, which were taken as van Houtryve was misrepresenting himself as a businessman. Shim’s conclusions that “North Korea is depicted as a foreign, secluded and dangerous place, where its people can only hope to escape from“ (p.78) echoes discourses on Orientalism and the need to perhaps save those who are helpless or, in the case of the North Korean citizens, those left without agency.

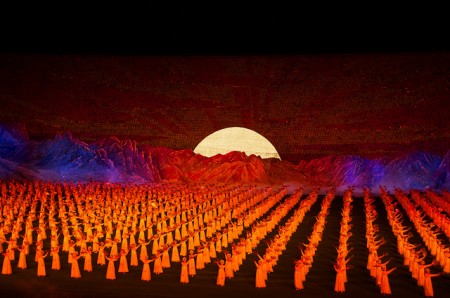

This vision of North Korea is challenged by Shim’s analysis of a second photographic report from the Associated Press Bureau in 2010, which presents images taken in Pyongyang during the 65th anniversary of the founding of the Workers Party, showing seemingly happy North Korean citizens participating in mundane activities, such as picnicking and attending a boxing game. A third photographic report published in the Guardian by Irina Kalashnikova also shows everyday North Korean people as images that “do not reduce the depicted people to mere passive participants who cannot do anything but suffer in a world of gloom” (p.87). One “elephant in the room” question remains, however: was this happiness as staged as when van Houtryve took pictures of empty streets on a freezing Sunday morning in Pyongyang with the intent to show how life in North Korea was at a standstill? This question is not really answered in the book, as it is beyond the remit of what Shim aims to achieve here, but is central to any work looking at sources and their utility. As such, the book could have, perhaps, been expanded to include more of a discussion of the intent of photographic reports, their impact on recipients (i.e. who is the target audience?), and whether the motivation to publish those pictures is more political than purely informational.

Lastly, Chapter 4 discusses satellite imagery and returns to a more political analysis of life in North Korea, as such images cannot show citizens in their everyday life, but can be equally, if not more, “subject to political appropriation and manipulation” (p.109). Shim rightly suggests that different types of satellite imagery lead to different types of interpretation. While anyone looking at a night picture of North Korea (in an interesting twist, the image chosen to illustrate the book cover is the very satellite picture showing the blackness of North Korea by night) will most likely equate the absence of light to the absence of energy (since, as Donald Rumsfeld is quoted a number of times in the book, “it says it all”), assessing whether or not a hangar houses nuclear weapons by looking at a daylight surveillance picture of a specific location requires specialized training and analytical skills, and all is not always as clear as one would hope for – especially given past “mistakes” when considering satellite pictures of supposed Iraqi Weapons of Mass Destructions. Hence, perhaps, satellite pictures do not “say it all” and might very well lead to more confusing outcomes, as such pictures are subject to a political will on the ground as well (in the case of North Korea, Shim suggests that staging for foreign satellite observation has taken place).

While Shim’s book cannot bring an answer to what the truth is when it comes to the “rea”’ North Korea, very few other volumes are able to do so anyway. Rather, the real value that Shim brings here is the discussion of techniques and ways in which staging take place, both in front of the camera and behind it. Shim’s final conclusion is the most important element of the book: “visual representations clearly address power” and this book is a useful companion piece when considering asymmetrical information and whose agenda one representation or another supports or weakens.

Bibliography

Bruner, Edward F. 2003. North Korean crisis possible military options. Derwood, MD: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress ; Distributed by Penny Hill Press.

Cha, Victor and David C. Kang. 2003. Nuclear North Korea: a Debate on Engagement Strategies. New York: Columbia University Press.

Downs, Chuck. 1999. Over The Line : North Korea’s Negotiating Strategy. Washington D.C: AEI Press.

Flake, Gordon L. and Scott Snyder, eds. 2003. Paved with Good Intentions: the NGO Experience in North Korea. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Gills, Barry. 1992. “North Korea and the Crisis of Socialism: The Historical Ironies of National Division.” Third World Quarterly no. 13 (1):107-130.

Kang, D. 2003. The Avoidable Crisis in North Korea, Orbis.

Liu, Ming. 2003. “China and the North Korean Crisis: Facing Test and Transition.” Pacific Affairs no. 76.

Mack, Andrew. 1993. “The Nuclear Crisis on the Korean Peninsula.” Asian Survey no. 33 (4):339-359.

Moon, Chung-in. 1996. Arms control on the Korean Peninsula : domestic perceptions, regional dynamics, international penetrations. Seoul, Korea: Yonsei University Press.

Moon, Chung-In and Jung-Hoon Lee. 2003. “The North Korean Nuclear Crisis Revisited: The Case for a Negotiated Settlement.” Security Dialogue no. 34 (2):135-151

O’Sullivan, Meghan L. 2000. “Sanctioning “Rogue States”.” Harvard International Review no. Summer:56-60.

Park, John S. 2005. “Inside Multilateralism: The Six-Party Talks.” Washington Quarterly no. 28 (4):75-91.

Park, Kyung-Ae. 2004. North Korea in 2003: Pendulum Swing between Crisis and Diplomacy, Asian Survey: University of California Press.

Perry, William J. 1999. Review of United States Policy toward North Korea: Findings and Recommendations. Washington, DC.

Quinones, C. Kenneth, James Clay Moltz. 2004. “Getting Serious About a Multilateral Approach to North Korea.” The Nonproliferation Review:136-144.

Rozman, Gilbert. 2007. “The North Korean Nuclear Crisis and U.S. Strategy in Northeast Asia.” Asian Survey no. 47 (4):601-621.

Satterwhite, David H. 1998. “North Korea in 1997: New Opportunities in a Time of Crisis.” Asian Survey no. 38 (1):11-23.

Smith, Hazel. 1999. “‘Opening up’ by default : North Korea, the humanitarian community and the crisis.” Pacific review no. 12 (3):453-478.

Snyder, Scott. 1996. A coming crisis on the Korean peninsula? the food crisis, economic decline, and political considerations. [Washington, D.C.]: U.S. Institute of Peace.

Starkey, Brigid. 2000. Negotiating with rogue states: what can theory and practice tell us? Paper read at International Studies Association Annual Meeting, at Los Angeles, California.

About The Author (Virginie Grzelczyk):

Dr. Virginie Grzelczyk is a lecturer in International Relations and the director of Postgraduate Programmes in Politics and International at Aston University, Birmingham, United Kingdom. Dr Grzelczyk’s work focuses on North Korea’s international relations, and her upcoming book North Korea’s New Diplomacy: Challenging Political Isolation in the 21st Century will be published by Palgrave in 2015.

For additional reading on this topic please see:

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s Weekly Dossiers and Security Watch.