This article was originally published by the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW) on 9 September 2016.

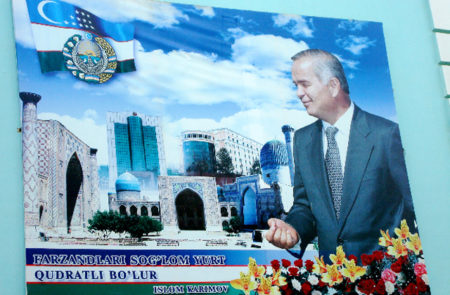

On 2 September (although unofficial reports cited 29 August as the date), the President of Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov died in Tashkent. Formally, the President’s duties are currently being carried out by the leader of the Senate, Nigmatilla Yuldashew (although he has not been sworn in as head of state), and elections to the post of president are to be held over the next three months. Due to the undemocratic nature of the system in Uzbekistan, the successor to Karimov will be decided by an informal fight for the leadership, and not the result of the election. Currently, the most likely successor seems to be the ruling Prime Minister, Shavgat Mirziyayev, who among other indications headed the funeral committee, received the foreign delegations who attended Karimov’s funeral on 3 September, as well as the President of Russia, Vladimir Putin, during his surprise visit to Samarkand on 6 September.

The formal transfer of power to Mirziyayev does not currently seem to be at risk. However, the consolidation of power and a new division of the informal influences in Uzbekistan will be a major challenge in view of the coming months. Another would be to prevent outbreaks of public dissent, which so far have been held back by violent repression and the fear of Karimov himself. Due to the country’s location and potential (including the potential for instability significantly enhanced by the death of Karimov), Uzbekistan is crucial for the security of the whole of Central Asia. The change of power in Uzbekistan therefore poses a challenge to external actors, and also opens a new chapter in Russian attempts to restore its dominance over the region.

Uzbekistan is the most populous country in Central Asia (it officially has 31 million inhabitants, and probably more) and the third largest in the post-Soviet area after Russia and Ukraine. Thanks to its central location, it dominated the region during the Soviet era, and expressed aspirations to regional hegemony after independence. Its political system, created by Karimov since he came to power in 1989, is extremely authoritarian and repressive, and corruption is prevalent at all levels of government. At present the country faces serious tensions of regional, ethnic (such as tensions with the Kyrgyz, its domestic Tajik minority) and social origin (caused by its archaic economic model and poor economic and social situations). The country has witnessed major crises (such as the attempt to seize power by Islamic fundamentalists in the Namangan region in 1990-1991), armed clashes and terrorism (attacks by the Islamic militant Movement of Uzbekistan in 2000) and mass protests (the revolt in Andijan in 2005). All of these have been bloodily suppressed by the government, and so far the stability of the country has been based on violent repression and total surveillance of the public, and effective control of the elites. At the same time, in contrast for example to Turkmenistan, informal groups within the elite are permanent actors on the domestic political scene. In addition, the Islamic factor plays a role; although independent Islam is combated through repression in Uzbekistan itself, Uzbek Islamic radicals and the organisations they have created are an essential part of the global jihad, including in Afghanistan and Syria.

Uzbekistan has tense relations with its neighbours (unregulated border issues, disputes about water resources, the problems of Uzbek minorities in border areas), which in the case of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan has at times teetered on the edge of open armed conflict. Uzbekistan is the largest regional challenge for Russia; it has consistently lead efforts to reduce its dependence on Russia, and in the past has periodically conducted explicitly anti-Russian policy, by drawing on support from the United States. In recent years, as a result of the withdrawal of the West from Central Asia and the deteriorating economic situation, there has been a fall-off in the ambitions of the Tashkent government.

The internal dimension – the struggle for power and the risk of destabilisation

The death of Karimov indicates a serious crisis and the need for modifications to the authoritarian political system, of which Karimov was the creator and the keystone. The unprecedented nature of these events, the opaque political system of Uzbekistan and the determination of individual actors are boosting uncertainty, both in the internal and external dimensions. Currently the most powerful player on the Uzbek political scene seems to be the long-time head of the National Security Service which supervises both the elite and the public – the 72-year-old Rustam Inayatov. Perhaps his efforts to push forward someone loyal to himself as Karimov’s successor will be most effective. A likely candidate for this is the Prime Minister since 2003, Shavgat Mirziyayev, who also enjoys the backing of Russia.

If the succession of power in Mirziyayev’s hands does not seem to be seriously threatened, its consequence will be an inevitable struggle for a new distribution of the profits within the ossified system of political corruption. The ongoing fight within the elites and the lack of a definitive solution to the question of the seizure of power has been suggested by a wide range of events, such as Putin’s unexpected visit, the meeting between Karimov’s daughter Lola and Alisher Usmanov, a Russian oligarch of Uzbek origin, or the regularly published (and denied) reports about the arrest of Rustam Azimov, the deputy prime minister and the challenger for Karimov’s legacy.

In the coming months, reshuffles and purges within the elites will be inevitable (the battle for the division of the spoils, and the elimination of competitors and losers). There may also be manifestations by the public: the socio-economic situation is bad, the scale of the problems and the tensions is high, and Uzbekistan has seen much turbulent social unrest in the past. At the same time, regardless of who will be the successor, the authoritarian nature of the state will most likely be preserved, although in the initial period, it is possible that there will be a mild departure in the symbolic dimension from Karimov’s policies (as was the case in Turkmenistan, for example).

If the struggle for power goes on too long, or the eventual successor is unable to consolidate his position, the extensive destabilisation of the country is possible, including internal conflict. Due to the demographic potential of Uzbekistan and its strained relations with its neighbours, this would also pose a challenge in the region as a whole. The chronic and structural nature of the problems existing in Uzbekistan means that even if Karimov’s successor succeeds in consolidating power, they will remain a threat to the stability of Uzbekistan, and the potential for destabilisation will increase (due, for example, to demographic pressure and the deteriorating economic situation in Russia, which hosts almost two million economic migrants from Uzbekistan).

The international consequences of Karimov’s death

The death of Karimov and the transfer of power present a number of challenges for external actors. At the regional level, the Central Asian states fear both the destabilisation of Uzbekistan, as well as Tashkent exploiting the problems in its relations with its neighbours to channel domestic tensions outwards. Such activities, aimed at strengthening the new rulers in Tashkent, could potentially include the escalation of border tensions with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, or aggravating the ethnic conflict between Uzbek and Kyrgyz inhabitants in the south of Kyrgyzstan.

Russia is currently the strongest player in Uzbekistan, although its capacity for effective action is definitely smaller than its needs and ambitions. For Moscow the death of Karimov, on the one hand, represents an opportunity to increase its influence in Uzbekistan. On the other hand, though, it is seen by the other players as test of its real strength in the region. In order to consolidate power and legitimise it at the regional level, Karimov’s successor will have to secure the support of Moscow, which creates room for Russia to take action. In this regard, we may expect an intensification of Russian pressure on Uzbekistan to rejoin the Collective Security Treaty Organisation, of which it has twice been a member (from 1994-9 and 2006-12). At the same time, how Russia copes with the changes in Uzbekistan will show its true strength in the region, and will outline both the model of Russia’s continued relations with China in the region (the economic influence of China, under Moscow’s supervision, in terms of security and ensuring fundamental stability), and its policies towards the issue of future successions of power (such as in Kazakhstan), as well as the integration of the post-Soviet area. The importance of the problem for Russia, and Moscow’s uncertainty at the succession’s outcome and awareness of its limitations, have been demonstrated by two visits – those of Prime Minister Medvedev at Karimov’s funeral and President Putin three days later.

Another actor is China, whose influence in Uzbekistan has been steadily rising since 2011, when Tashkent started a phase of intensive cooperation with Beijing. However, it is not as strong as in other countries in the region (such as Turkmenistan) and remains weaker than the influence of Russia. China’s main pillar is economic issues; the successor to Karimov will be forced to cooperate with Beijing due to the country’s poor economic situation and the lack of alternatives to Chinese support in financial terms (loans, investments). For China, the most important challenge is the stability of Uzbekistan; destabilisation would threaten the entire region, most tangibly supplies of Turkmen gas to China (the gas pipeline runs through Uzbekistan), and would have a negative impact on the stability of Xinjiang province, which is inhabited by Muslim Uighurs. The development of the situation in Uzbekistan will test the effectiveness of Beijing’s current policy in Central Asia, as well as Sino-Russian relations.

For its part, the involvement of the West in Central Asia (including Uzbekistan) is small, due to broader, strategic considerations, and the death of Karimov does not mean a return to a new ‘great game’ in the region. The challenge for the West, if the succession of power comes off smoothly, may come from an increase in the influence of Moscow in Uzbekistan and a change of Tashkent’s course in a more pro-Russian direction. If the process of the succession of power drags on, the West’s problem may lie in the destabilisation of the country. In this situation, due to Uzbekistan’s demographic potential, there could be a sharp and substantial increase in migratory pressures on EU countries from this direction.

About the Author

Józef Lang is a Central Asia analyst at the Center for Eastern Studies (OSW, Polish: rodek Studiów Wschodnich) in Warsaw, Poland.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit our CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Publications.