This article was originally published by OpenSecurity on 29 April, 2015.

Barring hurricanes, landslides and the occasional drug trafficking story, Guatemala doesn’t often reach our newspapers or TV screens. But in spring 2013, this small Central American country made the headlines when it put its former president on trial for genocide and crimes against humanity. The charges against General Efraín Ríos Montt and his Intelligence Chief, General Rodríguez Sanchez, were based on a military campaign in 1982-3 that targeted indigenous Mayan civilians. This was not a case of rogue troops, but sophisticated and brutal social engineering thinly masked as counter-insurgency against leftist rebels. Unlike Yugoslavia and Rwanda however, Guatemala was not given an international tribunal, or even a ‘hybrid’ war crimes court like Sierra Leone or Bosnia. Instead, justice came only 30 years later and from the most unlikely of places: an official state tribunal.

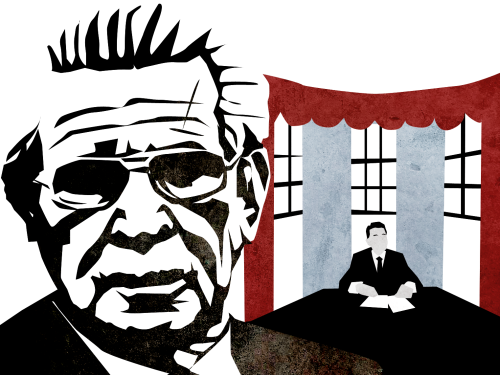

For 59 days, in a vast courtroom a huge audience sat divided like guests at some sinister wedding, surrounded by journalists, film teams, and police guarding the exits with machine-guns. Indigenous survivors and human rights activists crammed down one side, military veterans and their supporters down the other, with the diplomats and VIPs distributed democratically across the front rows. On 10 May, 2013–a sweltering Friday–the president of the three-judge bench, Yasmin Barrios, read the summary of their decision. When she announced that General Ríos had been found guilty and sentenced to 80 years the room erupted in tears, applause and disbelief. Shouting frantically over the noise, and unable to stop the press blocking her view of the general, Judge Barrios had the police block the exits to prevent him from being bundled out of a side door by his supporters. He was transported to Matamoros prison while General Rodríguez left for home, acquitted. This was headline news indeed: the first conviction of a head of state for genocide in credible criminal proceedings. (Ethiopia and Bolivia had done so, but following highly questionable legal proceedings).

Both the euphoria of the victims and the indignation of the general’s supporters were short lived. Days later, in a controversial decision the constitutional court partly rewound and started afresh from the lawyers’ closing arguments. The judges refused this extraordinary direction, since they had pronounced on the guilt and innocence of the accused and could not function as impartial tribunal. In protest or through fear, scores of other judges likewise refused to hear the case. Finally a new chamber was named and a full retrial ordered but it may never happen. The general’s health is failing and defence procedural motions continue the delays.

Attempts to uncover the past

This is one dramatic development in Guatemala’s long journey towards overcoming impunity and the denial of wartime atrocities. Comprehensive peace agreements ended the 36-year war between state forces and guerrilla groups in 1996, and since then Guatemalan victims and civil society groups have achieved major advances, uncovering a violent past and pursuing those responsible for atrocities. They have been supported by international solidarity movements, committed international donors, and, in recent years, some state prosecutors and judges.

Soon after the peace deal, two truth commissions broke new ground. The first was an initiative of the Catholic Church, the Recovery of Historical Memory (REMHI) project, considered by many to be a model of ‘truth-seeking’ mechanisms. This civil-society effort brought together historians, lawyers, sociologists and anthropologists, and trained field researchers who collected over 6000 testimonies. The resistance to exposing Guatemala’s past could not have been more brutally symbolised when two days after presenting the report in April 1998, the project’s 75-year-old leader Bishop Juan Gerardi was bludgeoned to death on his own doorstep with a concrete stone.

A UN-sponsored ‘official’ truth commission followed: the Commission for Historical Clarification. It had been negotiated as part of the peace agreements and was to make recommendations aimed at preventing future abuses. After similarly painstaking field research and analysis, its report confirmed the main findings of the earlier church study. More details emerged of the terrible crimes, and the report concluded that soldiers, police officers and state paramilitaries were responsible for 93% of human rights violations. It also delved into the complex social, economic, political and cultural context in which the war was fought. (The cold war was part of that context but Guatemala’s rulers and rebels were very far indeed from being proxy puppets). The reception for the UN report was less violent but equally dismissive. President Alvaro Arzú sat in the National Theatre in February 1999 while the commissioners presented their findings, then refused to accept the copy that was ceremonially handed to him. These two initiatives remain relevant now because they not only exposed human rights violations but also revealed the extent to which the country’s power structures–economic, judicial, political, religious–had been complicit in the atrocities.

Convictions were later secured in other key war crimes cases: executions, massacres and disappearances. Over time–with assistance of civil society investigators–prosecutors have successfully widened the net to include high-ranking officials. In January this year, the country’s former chief of police, already serving a prison term for the disappearance of a student, was convicted of murder and crimes against humanity due to his role in the attack by security forces on civilians taking refuge in the Spanish Embassy in Guatemala City in 1981. More prosecutions are under way including a landmark case of sexual slavery as a crime against humanity.

Judicial goalposts

How did Guatemala manage to make such strides? This country was a true ‘banana republic’, its brief democratic spring snuffed out in 1954 by a US-backed military coup following pressure from the United Fruit Company. Today it is a fragile state with enormous levels of impunity, poverty and corruption, but a window of opportunity opened in 2010 when Guatemala’s then president, Álvaro Colom, a centre-left progressive, appointed Dr Claudia Paz as Attorney General. Her administration has made unprecedented advances in combating organised crime but also made swift progress on human rights cases. Among the factors behind the latter, four stand out.

First, Guatemalan law allows what is effectively a co-prosecutorial role in criminal prosecutions for victims and civil society groups as querellantes (plaintiffs). Human rights groups seized on this, documenting atrocities and litigating cases. One of them, the Centro para Acción Legal en Derechos Humanos, launched a war crimes prosecutions project in 1997. After consulting around 70 villages, 23 agreed to a legal case against General Ríos Montt and others. They formed the Asociación para Justicia y Reconciliación (AJR) which has proved central to maintaining solidarity: this was a collective response to collective violence and AJR members come from indigenous groups across the highlands. After the discovery of a key military document, the prosecution narrowed the case to only the Ixil people but survivors welcomed the conviction of Ríos Montt as a victory for all indigenous people.

Second, genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity were criminalised in Guatemala in 1973, so there was no question of retroactivity, a problem for many other post conflict countries. Third, the amnesty law negotiated as part of the peace deal excluded international crimes like genocide and torture. And finally, Guatemala boasts many extraordinarily brave victims, local lawyers, prosecutors and judges. Despite the Constitutional Court’s judicial vandalism, the genocide verdict moved the goalposts. The national legal system showed itself capable of producing high-quality prosecutions of international crimes.

Since the trial of the Argentine Junta in 1986, through Guatemala, Peru, Uruguay, Bolivia and Colombia, Latin America has led the world in domestic prosecutions of international crimes and today offers a rich experience of how collective violence has spawned collective responses from victims and civil society. Language has often been a barrier to the exportation of this experience, but many English language resources are now available and ideal for anyone interested in truth and impunity issues, and as teaching resources. Justice developments in Guatemala and worldwide are covered on the excellent blog International Justice Monitor, and the website of the International Center for Transitional Justice. For film footage with subtitles look for the “Dictator in the Dock” series. In-depth analysis can be obtained in the Digest of Latin American Jurisprudence on International Crimes.

Future concerns

So where does this leave Guatemala? Yes, progress has been made, but the vast majority of survivors are still without justice, information or acknowledgment, among them leading activist Helen Mack, whose sister Myrna was murdered in 1990. Yet even if all the atrocities were to be adequately investigated, it would melt only the tip of a large and multifaceted iceberg standing in the way of the country becoming a rights-respecting democracy. The power structures that supported successive military dictatorships have survived the war and the peace process intact. They continue to form strategic alliances with military pressure groups, and organised crime, and they oppose not just trials and truth commissions but any attempt to bring economic, social and cultural rights to the majority of the population. The reaction from vested interests to the progress in prosecutions of all types under Dr Paz has been a coordinated strategy to control the judiciary by co-opting the judicial appointments process.

History now seems in danger of repeating itself, and truth and impunity is very much part of the battleground. Guatemalan President Otto Pérez Molina, a former army commander implicated in the crimes, told the press during the trial itself that there was no genocide in Guatemala and shortly after General Ríos’s conviction, Congress passed a resolution declaring that “genocide was not committed in Guatemala.” Judge Barrios was suspended, Attorney General Dr Paz was forced to step down early and was not re-elected, and a far-right group called Foundation Against Terrorism now issues threats and raises spurious legal actions against these officials and anyone involved in human rights cases–most recently the prosecutor in the Ríos Montt case, Mr Orlando Lopez. Some 75% of Guatemalans live below the poverty line and discrimination against indigenous Mayans and minority groups is endemic. It is hard to see the peace dividend nearly 20 years after the war ended. The causes of the war persist and organised crime is new addition to an already dangerous mix. A return to mass violence remains a real possibility as Guatemala approaches its next presidential election this September.

Guatemalan civil society is a resilient beast though, fighting on many fronts at home and abroad. It lobbied the UN and Guatemalan government to create the world’s first hybrid investigation body for organized crime, the International Comission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). in 2008. Further lobbying resulted in the US Congress tying military aid to government cooperation to future war-crimes trials and opening of archives. The campaign for indigenous people’s rights in Guatemala, implicating foreign mining companies, led to the world’s first Peoples International Health Tribunal in 2012.

Lets hope the next headlines from Guatemala are good ones. For now, the last word goes to the AJR President Benjamin Jerónimo: “The verdict recognizes the rights of peoples to resist, to chose how to live, and to express their will which must be heard. It is our obligation to fight for justice so that survivors are recognized as human beings … This conviction is important, but only part of a larger struggle.”

Susan Kemp is a lawyer specialising in international criminal law and human rights. From May 2015 she will serve as a Commissioner on the Scottish Human Rights Commission.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.