In today’s blog, Michael Chase and Jeffrey Engstrom face off against Roger Cliff on China’s ongoing military reforms. The two ‘optimists’ believe the reforms will help blunt corruption, strengthen civilian control over the PLA, and modernize the armed forces. Roger Cliff, in contrast, argues that the reforms won’t resolve two of the PLA’s most glaring weaknesses – its limited joint capabilities and the continued dominance of the army.

China’s Military Reforms: An Optimistic Take

This article was originally published in Joint Forces Quarterly 83 by National Defense University Press on 1 October 2016.

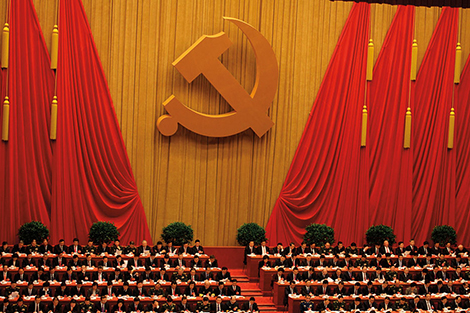

China is implementing a sweeping reorganization of its military that has the potential to be the most important in the post-1949 history of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).1 Xi Jinping, who serves as China’s president, general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, and chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), seeks to transform the PLA into a fully modernized and “informatized” fighting force capable of carrying out joint combat operations, conducting military operations other than war (MOOTW), and providing a powerful strategic deterrent to prevent challenges to China’s interests and constrain the decisions of potential adversaries. Scheduled for completion by 2020, the reforms aim to place the services on a more even footing in the traditionally army-dominated PLA and to enable the military to more effectively harness space, cyberspace, and electronic warfare capabilities. Simultaneously, Xi is looking to rein in PLA corruption and assert his control over the military.

Brief Overview of the Reforms

China unveiled the long-anticipated organizational reforms in a series of major announcements beginning on December 31, 2015, when it subordinated the ground force to an army service headquarters, raised the stature and role of the strategic missile force, and established a Strategic Support Force (SSF) to integrate space, cyber, and electronic warfare capabilities. On January 11, 2016, Xi announced “a dramatic breakthrough . . . in the reform of the military leadership and command system” that discarded the PLA’s four traditional general departments in favor of 15 new CMC functional departments.2 Next, the reorganization eliminated China’s seven military regions (MRs) and converted them into five theater commands. This part of the restructuring is intended to enhance the PLA’s readiness and strengthen its deterrence and warfighting capabilities. In addition, the CMC released a “guideline on deepening national defense and military reform,” which states that under the new system, the CMC is in charge of overall administration of the PLA, People’s Armed Police, militia, and reserves; the new joint war zone commands focus on combat preparedness, and the services are in charge of development (presumably of personnel and capabilities).

Likely Benefits of the Reforms

The reforms are likely to offer benefits in several areas, including achieving enhanced jointness, optimizing organizational structures for combat, and ensuring information dominance.

Achieving Enhanced Jointness. One important aspect of the reforms is that the ground force is becoming a real service. Historically, the PLA’s ground service component lacked a headquarters and instead dominated the entire military by controlling all four of the PLA’s general departments, which doubled as its de facto headquarters. Under the new system, however, the army will now possess its own headquarters—referred to as the PLA Army Leading Organ—and will be on par with the PLA’s naval, air, and newly formed strategic missile service.

The main goals in this respect appear to be to reduce army domination and improve the PLA’s jointness. To this end, giving the ground force its own headquarters appears to be an important step in the direction of positioning the PLA away from the dominance of army-centric thinking and leadership. It also emphasizes the contributions of other services, and, along with the reduction of 300,000 troops Xi announced in September 2015, it likely cuts fat and frees resources to build air force, rocket force, and navy capabilities.3 Another benefit of the ground force focusing more heavily on its own requirements rather than those of the entire PLA could be accelerating efforts to transform it into a leaner force more capable of carrying out joint combat operations and MOOTW.

Optimizing Organizational Structures for Combat. The second major benefit of the reforms derives from the elimination of MRs and their replacement with theater commands. The purpose of reorganizing the military regions into a smaller number of theater commands is to improve the PLA’s ability to prepare for and execute modern, high-intensity joint military operations. For many years, PLA officers have perceived the old MR-based command structure as outdated and not well suited to winning the kinds of conflicts they think the PLA may need to be prepared for in the future.

Theater commands now directly focus on the specific strategic directions determined by potential external threats. Instead of two MRs dealing with a hypothetical India conflict, there is now one. Instead of three MRs bordering Russia, there are now only two, and one shares only an approximately 30-mile border. In this way, the external threat environment arguably has shaped the development of the theaters in a profound way that never appeared to be a rationale for any of the previous and varied configurations of MRs since the founding of the PRC. Seams, however, still exist. The Sino-Vietnamese border region appears unchanged by this restructuring, with two theater commands replacing two military regions.

Transition from peacetime to wartime command will be easier. Under the former system, the MR commander was not necessarily the wartime theater commander. This individual would likely be appointed by the CMC and sanctioned to set up a theater that might span multiple MRs.4 Under the new system, the theater command for wartime is already stood up. The theater command is the “top joint operational commanding institution,” and therefore the theater commander is also the joint forces commander.5 The theater commander and his staff presumably are already keenly attuned to the particular threats in their command and, other than potential relocation to a wartime command post, are immediately ready to prosecute a conflict with forces currently existing within the theater command and those that may have been sent from other theater commands.

In addition, the theater command structure allows the PLA to truly implement the active defense strategy as a preemptive posture. The former system of enacting wartime theaters placed a premium on China either starting a conflict itself or anticipating conflict well before it occurred. Conflict or aggression that was either unforeseen or occurred with little lead time immediately placed China into a reactive and defensive posture. Early iterations of the People’s War strategy recognized China’s own limitations in its ability to fight technologically superior adversaries under these circumstances, tacitly accepting that potential invaders would necessarily encroach upon China’s territorial sovereignty. Though substantial military modernization efforts by the PLA over the last few decades had already rendered Maoist doctrine on this topic moot, the theater command structure provides the required organizational framework to enact an active defense posture.

Ensuring Information Dominance. A third major benefit could be realized if the creation of the Strategic Support Force—which is responsible for cyber, space, electronic warfare, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance—offers improved flexibility and responsiveness that enhance the PLA’s ability to fight multi-domain conflicts. This recognizes the need for such forces, places them within a clear command structure, and likely provides additional resources and intra-service stature (from a general staff department to a force).

Indeed, this may be the least surprising change, as the emphasis on information warfare has captured the attention of the PLA since at least the mid-1990s. The current conception of “winning informationized local wars” recognizes the centrality of information and the information domain as a battlefield in modern warfare. The creation of such forces is driven by the reality that national-level assets must perform many information functions in warfare. Furthermore, it would be unrealistic and unnecessary to recreate many of these functions and capabilities under each theater command. Lastly, many of the SSF’s capabilities in the cyber and space domains, if used, could be extremely escalatory. For all of these factors, the SSF appears to be directly (and appropriately) subordinate to the CMC rather than a theater command or service. However, it appears likely that units within the theaters will be under operational control of the theater commander.6

Success Likely Despite Expected Opposition

Xi’s anti-corruption campaign is part of an effort aimed at strengthening party (and his own) control over the PLA. When Xi assumed power in November 2012, he vowed to fight both “tigers” and “flies”—a reference to taking on corrupt leaders at the highest levels as well as lower level bureaucrats engaged in corrupt practices throughout the Chinese system, and the PLA would be no exception. The first shot over the bow came against the tigers. In 2014, Xi arrested a former CMC vice chairman, Xu Caihou, for participating in a “cash for ranks” scheme. After expelling Xu from the party, Xi followed up in 2015 with the arrest and purge of another former CMC vice chairman, Guo Boxiong, on similar charges. The arrests were unprecedented in that Xu and Guo were the two highest-ranking officers in China’s military when they served as CMC vice chairmen, and their arrests marked the first time the PLA’s highest-level retired officers faced corruption charges. As of early March 2016, Xi’s anti-corruption campaign had reportedly resulted in the arrest of at least 60 military officers, although the actual numbers could be higher.

Another reflection of Xi’s determination to strengthen his control came when he drew a direct line between the era of Mao Zedong and the present at a major meeting in November 2014. In commemoration of the 85th anniversary of the “Gutian Congress,” at which Mao first affirmed the “party’s absolute control over the military” in 1929, Xi convened 420 of his most senior officers to meet in the small town of Gutian in southeastern Fujian Province.7 This was believed to be the first time a PRC leader reconvened military leadership at Gutian since Mao’s famous meeting there—symbolism that was certainly not lost on the top brass. Prior reading material reportedly reaffirmed the unassailable and preeminent position the party has over the military. This set the stage for Xi to implicitly convey to all in attendance that they too could become victims of his anti-corruption campaign, just as General Xu had a few months earlier, if they refused to toe the line. Indeed, the anti-corruption campaign is probably the most important source of Xi’s power over the PLA.

Unanswered Questions

While the reorganization appears to offer a number of important benefits to the PLA, several important questions remain unanswered. These include:

- What impact will the anti-corruption campaign have on military effectiveness? Specifically, is it weeding out the bad apples, or does it have a chilling effect on potentially dynamic senior officers that the PLA will need if it is to be successful in fighting and winning wars?

- Will ground force personnel continue to dominate most of the top positions in the PLA even under the reforms, or will this change over the next several years as a result of future retirements and promotions under the reforms? For example, will a PLA Navy, PLA Air Force, or PLA Rocket Force officer serve in a position such as commander of one of the new theater commands or director of the new Joint Staff Department under the CMC?

- Does the focus on the reorganization and changes such as reshuffling of former MR commanders to new theaters cast doubt on the PLA’s ability to prosecute conflict at its borders, at least in the short run?

- Can the PLA ever move from a system of personal power bases/loyalty structures to one of a highly functional bureaucracy in which such dynamics matter very little or not at all?

Conclusion

Xi Jinping has ordered the PLA to embark on a sweeping reorganization aimed at transforming it into a leaner and more modern military that is more capable of carrying out joint operations. There are clear indications that Beijing expects some internal opposition to the reorganization, but Xi Jinping’s unprecedented anti-corruption campaign probably gives him the leverage he needs to overcome entrenched opposition. The reorganization will have a major impact on the PLA’s ability to prepare for and execute its main functions of strategic deterrence, combat operations, and MOOTW.

Importantly, despite some speculation to the contrary, Xi’s assertion of control over the military in the form of the anti-corruption campaign and organizational reforms is more likely to enhance than it is to impede the PLA’s ongoing modernization efforts. Part of Xi’s “China Dream” is to produce a strong military capable of deterring or, if necessary, taking on powerful potential adversaries, including even the United States.

Xi not only wants a PLA that demonstrates utmost loyalty to the party, but he also wants a far more competent and operationally capable PLA by 2020, one that is commensurate with China’s status as a major world power and capable of protecting China’s regional and global interests. If his aspirations are realized, Xi’s reformed PLA will soon be capable of posing an even more potent challenge to China’s neighbors and to U.S. objectives and strategy in the region.

Notes

1 See, for example, Phillip C. Saunders and Joel Wuthnow, China’s Goldwater-Nichols? Assessing PLA Organizational Reforms, Strategic Forum 294 (Washington, DC: NDU Press, April 2016), available at <http://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratforum/SF-294.pdf>; and Kenneth W. Allen, Dennis J. Blasko, and John F. Corbett, Jr., The PLA’s New Organizational Structure: What is Known, Unknown and Speculation (Part 1), China Brief 16, no. 3 (Washington, DC: The Jamestown Foundation, February 4, 2016).

2 Prior to the reorganization, these were the General Staff Department, General Political Department, General Logistics Department, and General Armaments Department. These new functional departments under the Central Military Committee (CMC) include the General Office, Joint Staff Department, Political Work Department, Logistic Support Department, Equipment Development Department, Training and Administration Department, National Defense Mobilization Department, Discipline Inspection Commission, Politics and Law Commission, Science and Technology Commission, Office for Strategic Planning, Office for Reform and Organizational Structure, Office for International Military Cooperation, Audit Office, and Agency for Offices Administration.

3 Evidence of this is having an immediate trickledown effect on the enrollment at the PLA’s military schools; one newspaper article reports that schools focusing on ground force competencies such as infantry and artillery will see a reduction in admission of 24 percent whereas aviation, missile, and naval schools will increase admissions by 14 percent. See “PLA Restructuring Changes Focus at Military Schools,” China Daily, April 28, 2016.

4 This individual could be a commander of one of the military regions adjacent to conflict as it was with Xu Shiyou and Li Desheng for the Southern and Northern Theaters, respectively, during the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War, or the CMC could appoint a senior general officer from another command entirely, as it did with Peng Dehuai during the Korean War.

5 “Spokesperson: PLA’s Theater Command Adjustment and Establishment Accomplished,” China Military Online, February 2, 2016.

6 Saunders and Wuthnow, 3.

7 James C. Mulvenon, “Hotel Gutian: We Haven’t Had That Spirit Here Since 1929,” China Leadership Monitor, no. 46 (Winter 2015).

About the Authors

Dr. Michael S. Chase is a Senior Political Scientist at RAND, Adjunct Professor in the School of Advanced and International Studies at The Johns Hopkins University, and Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University.

Jeffrey Engstrom is a Senior Project Associate at RAND.

Chinese Military Reforms: A Pessimistic Take

This article was originally published in Joint Forces Quarterly 83 by National Defense University Press on 1 October 2016.

On the evening of May 21, 1941, the German battleship Bismarck, escorted by the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, departed the Norwegian port of Bergen, intending to conduct commerce raiding against Allied merchant shipping in the Atlantic Ocean. The Bismarck was the world’s largest warship in operation at the time and proved to be virtually unsinkable by naval gunfire; it ultimately absorbed more than 400 direct hits from naval guns, roughly a quarter of which were main battery rounds from other battleships, without sinking. And yet less than 6 days into its first combat mission, the Bismarck had nonetheless been sunk. Better armor or a more powerful armament might have made the Bismarck even more dangerous and difficult to sink, but would not have prevented it from being sunk. Similarly, recent changes to the organizational structure of China’s military have made clear improvements, but do nothing to address its most important weaknesses.

Recent Changes

Over the past few months the leadership of China’s military has announced several major changes to the organizational structure of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). One change has been the dismantling of the four “general departments” that formerly served as both the headquarters of the PLA Army (PLAA) and as a joint staff for the entire military. Most joint staff–type functions have been moved to the Central Military Commission (CMC) while a separate PLAA headquarters has been created, comparable to the headquarters of the PLA Navy, Air Force, and Rocket Force (formerly known as the Second Artillery Force), to oversee the PLAA. In addition, the Rocket Force has been elevated in stature from an independent branch (兵种) to a full-fledged service (军种). A new organization, the Strategic Support Force (战略保障部队), has been created and is apparently independent of the four services, although precisely how it will be organized and function are unclear as of this writing.

The other major area of organizational change has been the replacement of the former seven military region commands (军区) by five theater commands (战区). Aside from the enlarged geographic areas of responsibility, a key difference between the new theater commands and old military region commands is that the former are explicitly designed to be joint headquarters similar to the geographic combatant command headquarters of the U.S. military. Under the old system, although the commanders of the military region air forces (MRAFs) and, if applicable, PLA Navy fleets who were based in a military region were deputy commanders of the military region, the MRAFs and fleets themselves were not subordinate to the commander of the military region but rather to the headquarters of the PLA Air Force and Navy. Now each theater command has established a joint command post and, presumably, at least in a small-scale contingency, the PLA Air Force, Navy, and Rocket Force forces in a region would be under the command of the theater commander.

Assessment

These changes have rightly been recognized as significant steps toward resolving some longstanding problems caused by the PLA’s previous organizational structure, particularly in the area of “jointness.” Creating a separate PLAA headquarters and moving the joint staff functions previously performed by the general departments to the CMC eliminate the inherent institutional bias caused by having a single organization responsible for both PLA army specific and joint functions. Elevating the PLA Rocket Force to the level of a full-fledged service increases its stature and influence relative to the other services in general and helps counterbalance the PLAA dominance in particular. The creation of the Strategic Support Force may further dilute the influence of the army. And creating theater commands, in the place of collections of single-service organizations that just happen to be located in the same place, means that the PLA can now conduct truly joint operations at the theater level.

These changes have rightly been recognized as insufficient to achieve true jointness. The key remaining obstacle is continued army dominance of PLA command organizations, even if those organizations are now officially joint. Once reason for this is that even if all 300,000 troops to be eliminated from the PLA, as announced in September 2015, are members of the army, more than half of the remaining PLA personnel will still be army personnel. Thus everything else being equal, on average more than half the qualified personnel available to fill positions in joint organizations will be from the army. Continued army dominance appears to be the result of more than just the numbers of available personnel, however, as all the commanders and four of the five political commissars of the ostensibly joint theater commands are PLAA officers.1

Even if the dominance of the PLAA is gradually reduced over time, however, the PLA faces more serious challenges than a lack of jointness, and the recent organizational changes do nothing to resolve these challenges and, in some cases, make them worse.

The PLA has made significant improvements in many areas over the past two decades in an effort to transform itself into an effective, modern fighting force. These improvements have been greatest in the areas of personnel quality, weaponry, and training. Nonetheless, fundamental flaws remain that, in a conflict, would likely prevent the PLA from effectively employing its weaponry, personnel, and training. Most crucially, the operational doctrine of the PLA is inconsistent with both its organizational culture and its organizational structure.

Organizational Structure

Organizational theorists use several general characteristics to describe an organization’s structure. One is organizational height (that is, the number of organizational layers between the lowest ranking person and the highest ranking person in an organization). To operate at maximum efficiency, an organization should have the smallest number of layers needed to ensure that supervisors at each level have no more direct subordinates than they can adequately manage. The optimal height of a specific organization depends on its size and the nature of its activities, but in general adding organizational layers tends to reduce efficiency. In this regard the PLA’s recent structural changes do not appear to have made a significant difference. One organizational level, the general departments, was eliminated, but their functions were simply moved up to the CMC—in effect adding a layer to the CMC’s chain of command—and horizontally, in the creation of the PLAA headquarters. Comparison with the U.S. military, however, suggests that the PLA’s structure is not overly “tall.” The PLA has roughly the same number of organizational layers between top commanders and frontline troops, even though the PLA will have roughly 50 percent more personnel than the U.S. military even after the current round of troop reductions. Thus, there does not appear to be a need for the PLA to eliminate organizational layers.

Other characteristics used to describe an organization’s structure are its degrees of centralization, standardization, and horizontal integration. The type of organization that is optimal for a military in these dimensions depends on the nature of its operational doctrine. If the military’s doctrine emphasizes maneuver and indirection, such as the Israeli military and German army during the early part of World War II, then it needs an organization that is decentralized, has a low degree of standardization (that is, allows its personnel to deviate from standard practices as the situation warrants), and has a high degree of horizontal integration so that field commanders can coordinate directly with their local counterparts in other units and services without having to get approval all the way up and down their respective chains of command. But if the military has a doctrine that emphasizes direct engagement (that is, defeating an enemy through direct assaults on his main forces, such as most of the U.S. and Soviet armies during World War II), then it needs an organization that is highly centralized, has a high degree of standardization, and has a low degree of horizontal integration.

Since 1999 the PLA has had a doctrine that emphasizes indirection and maneuver. Authoritative PLA publications advocate avoiding directly engaging an adversary’s main forces and instead conducting “focal point” strikes on targets such as command and control centers, information systems, transportation hubs, and logistics systems, with the goal of rendering the adversary “blind” and “paralyzed.” The transient and unpredictable nature of opportunities to attack such targets means that effectively implementing this doctrine requires an agile organization that is decentralized, has a low degree of standardization, and has a high degree of horizontal integration. By all accounts, however, the PLA has precisely the opposite type of organization. The PLA is highly centralized, with low-level officers and enlisted personnel having limited authority to make their own decisions. The PLA is highly standardized, with minimal latitude for individuals or sub-organizations to deviate from prescribed practices. And the PLA has low levels of horizontal integration, with most personnel spending their entire careers within a single chain of command and most units having only infrequent contact with units outside their chain of command. Thus there is a fundamental incompatibility between the nature of the PLA’s doctrine and its organizational structure.

The recent structural changes to the PLA have done little to alter this incompatibility. The joint command posts set up in each theater employ tens of personnel drawn from each of the services. For many of these personnel, working in the command post will be the first time they have had to work with personnel from another service. If the average term of assignment to a joint command post lasts, for instance, 3 years, then in 15 years’ time there may be several thousand PLA members, mostly officers, who are experienced working with personnel from other services and branches. This will expand their personal networks beyond their own chains of command and strengthen their ability to communicate and coordinate their actions with members of other branches and services. These will represent a tiny percentage of the several hundred thousand officers and two million members of the PLA, however, and will not address the fact that, unless current PLA personnel practices change, the vast majority of PLA members will not have experience working in, or with, another division, much less a unit in a different military region or service than the ones in which they have spent their entire career.

Other aspects of the recent structural changes, moreover, are designed to increase the centralization of the PLA, not decrease it. Abolishing the general departments and moving their functions to the CMC, although this does not change the number of organizational layers between them and the commander of the China’s armed forces (President and CMC Chairman Xi Jinping), will tend to have the effect of increasing central control over these functions. In addition, the PLA has adopted a “CMC chairmanship responsibility system,” under which “all significant issues in national defense and army building” will be “planned and decided by the CMC chairman,” as compared to previously, when senior officers at the CMC, general departments, and military regions were allowed to make some of these decisions on their own.2 The effects of this movement toward more centralized control at the upper levels of the PLA are likely to permeate down to lower levels, resulting in an organization that is even more centralized than previously. Thus the recent structural changes to the PLA have not only not resolved the fundamental inconsistency between its operational doctrine and its organizational structure, but they also have made the situation worse.

Organizational Culture

The recent structural changes do not address another fundamental flaw in the PLA, which is an incompatibility between its operational doctrine and its organizational culture. Just as a military with a doctrine that emphasizes maneuver and indirection needs an organizational structure that is decentralized, has low levels of standardization, and has high levels of horizontal integration, it needs an organizational culture that values initiative, innovation and creativity, adaptability and flexibility, and risk-taking. But these are among the qualities that are least valued by PLA organizational culture. The recent structural changes, moreover, the effects of which are to increase central control over the PLA, are likely to result in a further discouragement of initiative, innovation and creativity, adaptability and flexibility, and risk-taking. Thus, the recent structural changes have likely made this weakness of the PLA worse as well.

Conclusion

The Bismarck’s sinking resulted from a fundamental mismatch between its capabilities and those of what turned out to be the dominant platform for conducting naval warfare in 1941—the airplane. The Bismarck was unable to defend itself against attacks by a total of just 24 British torpedo bombers that resulted in three torpedo hits, one of which jammed the Bismarck’s port rudder, rendering the ship unmaneuverable. Not only did the jammed rudder prevent the Bismarck from escaping the two British battleships and two heavy cruisers that were pursuing it, but it was also unable to return fire when they did. As a result, even though the British ships were unable to sink the Bismarck with gunfire, they were able to put its main armament out of action, set the entire ship aflame, and eventually sink it with torpedoes launched from close range. The recent changes to the organizational structure of the PLA will unquestionably improve its capabilities to conduct military operations, but without fundamental changes to its organizational structure and organizational culture or, alternatively, to its operational doctrine, the PLA will be unable to take full advantage of the considerable improvements it has made to its personnel, weaponry, and training over the past two decades. This is not to say that the PLA would not be a dangerous and formidable foe for the armed forces of the United States or other nation. After all, the Bismarck sank a British battlecruiser and damaged a battleship before itself being sunk, but it would be a flawed giant, vulnerable to an adversary that can exploit its weaknesses.

Notes

1 The fifth political commissar spent most of his career in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) before transferring to the PLA Air Force.

2 See Phillip C. Saunders and Joel Wuthnow, China’s Goldwater-Nichols? Assessing PLA Organizational Reforms, Strategic Forum 294 (Washington, DC: NDU Press, April 2016), 6, available at <ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratforum/SF-294.pdf>.

About the Author

Dr. Roger Cliff is a Senior Research Scientist at the Center for Naval Analyses.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit our CSS Security Watch Series or browse our Publications.