Declaring a state of emergency opens the door to an exceptional world, one in which government power is temporarily prioritized over individual rights. Unfortunately, many countries (see examples below) have made the exception a permanent rule.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) recognizes each state’s right to declare a state of emergency in times of public crisis that pose a direct threat to the nation. This allows the state to derogate from certain human rights obligations under the Covenant. Declaring a state of emergency grants governments exceptional powers, thus allowing them to curtail certain individual rights.

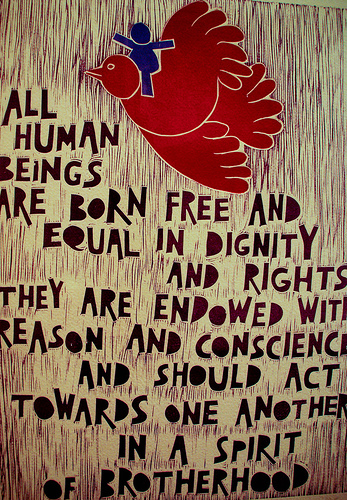

Although certain rights are non-derogable even at a time of national emergency – among others, the right to life, prohibition of torture, freedom from slavery, the right to recognition before the law – governments can limit the freedom of the press, deploy armed forces domestically, search homes without a warrant, confiscate private property, and arrest without charges.

In order to avoid governmental abuse, the ICCPR makes clear a state of emergency must be guided by certain principles. First, the crisis at hand must be of present and real danger to the state’s political or territorial existence. Second, it must be temporary, meaning that states can only declare a state of emergency for as long as the crisis is still present. And third, the state of emergency must be clearly declared and communicated both to the domestic population and to the international community.