This article was originally published by Political Violence @ a Glance on 1 May 2019.

The Easter morning attack in Sri Lanka reminds us that, when it comes to terrorism, governments often want to reduce the amount of media attention attackers receive. This is why the Sri Lankan government initially withheld the names of the attackers who killed nearly 300 and injured many more. The desire to deny perpetrators publicity is also why New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Arden publicly refused to utter the name of the gunman who killed fifty people attending mosques in Christchurch. A similar impulse can be seen in US President Barack Obama’s attempt to downplay the threat from ISIS by calling them the “jayvee team.”

But can governments actually discourage terrorism by influencing the mass media’s attention? Our research suggests the answer is not much, although we do not address the efficacy of these policies specifically. Nevertheless, we have a potentially useful way of thinking about the promise of counterterrorism policies that influence media attention.

In recently published research on the relationship between foreign press attention and the incidence of deadly foreign terrorist attacks, we find countries that receive more attention from the international press suffer more deadly foreign terrorist attacks; however, we find that the benefits of reducing press attention are small. For instance, if the United States—the world’s most media-saturated country—somehow turned itself into one of the world’s least covered countries, it would experience one fewer deadly terrorist attack every two years.

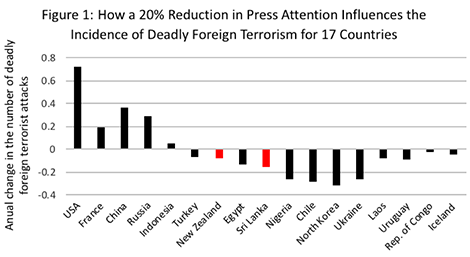

Smaller reductions in foreign press attention have more variable consequences. In most cases, a 20% reduction in foreign press attention produces no benefit for a country like the US. In some situations, the US could reduce the amount of attention it receives and still experience a slight increase in attacks. In contrast, New Zealand and Sri Lanka, countries that receive middling levels of coverage from foreign wire services like Reuters, can reduce their susceptibility to deadly foreign attacks by encouraging journalists to report elsewhere (see Figure 1).

How can this be? Thinking about the way competition for foreign press coverage is structured helps solve the puzzle. Foreign terrorist groups and other publicity-seekers compete with one another for press attention in the hopes that their actions will make the news. Like Olympic competition, however, the “publicity prizes” terrorist organizations compete for vary in quality. Front page coverage in a national newspaper like The New York Times is more valuable to terrorists than coverage in a local newspaper. The prizes are also limited in quantity. Many groups are denied coverage of any kind even though they expend resources and effort to compete for attention. Economists refer to this kind of situation as a rank-ordered tournament.

This arrangement encourages terrorist organizations to use deadly force more often in order to outbid others for coverage. It also encourages skillful foreign terrorist organizations to focus their attacks on those countries that receive the greatest attention from foreign media outlets. Getting the best coverage is not simply a matter of conducting the most outrageous attack— groups have to capture the attention of reporters who cover the locations that interest audiences.

The incentive for terrorist organizations to target attacks in “publicity-rich” countries tends to discourage less skilled terrorist organizations from competing in those arenas in the first place. The odds of getting press attention in these elite tournaments are too low to justify expending resources and effort. The result is that some groups either stop pursuing press coverage at all or attack in places where it is easier to get coverage, even if that coverage is not headline news.

Concretely, this means that countries that receive middling levels of press attention stand to gain by reducing press attention further. Conversely, countries at the upper and lower levels of press attention get much less benefit from reducing the attention afforded to terrorist organizations.

In the present case of Sri Lanka, this means that a policy of denying terrorists attention could work because Sri Lanka is not a country that ordinarily receives high levels of press attention. On the other hand, it is unclear that denying terrorists notoriety will reduce overall press attention to Sri Lanka by much, raising questions about the security benefits of this approach.

About the Authors

Crystal Shelton is a lecturer in the Department of Political Science at Christopher Newport University.

Erik Cleven is associate professor in the Department of Politics at Saint Anselm College.

Aaron Hoffman is associate professor in the Department of Political Science at Simon Fraser University.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS website.