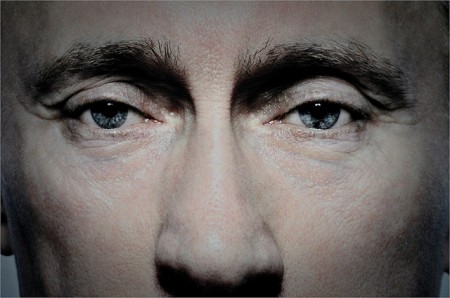

There are those, not least in the West, who hope or even suppose that Vladimir Putin’s reincarnation on 7 May as President of Russia will mean a fresh start.

On the face of it, he is well placed to make one. The new Duma is structured for subservience, the Russian economy is doing pretty well, and the protest movement has lost the momentum it enjoyed from December 2011 to March this year. Putin’s personal dominance over the small group of his associates that rule the country has been reinforced.

That also means of course that his answerability for the future course of events has increased too. It would be unusual for any man embarking on what in effect is his fourth term of office to change his underlying ideas. Dimitry Medvedev, who used a different vocabulary, has been set aside as a tame Prime Minister in waiting. It is probable that the next administration President Putin sponsors will for the most part be a reshuffle of well-used cards. Putin’s campaign offering was stability, not change.

The 2011/2012 electoral cycle was nonetheless a stage in a continuing process which has increased the gap between the ruling group and substantial sections of Russian society – not just the urban middle class. Putin’s hold as a national leader beyond mere politics has been damaged. He will need to show purpose and convey a sense of renewal if he is to regain his previous authority, and certainly so if he plans to return yet again to the Kremlin in 2018.

Economic Road Map: Without the Politics?

The thrust of Putin’s proposals, which are to be set out in detail in the implementation road map that he has promised to issue, appear to rely on the state to take the lead in diversifying and reinvigorating the economy. Putin has called for the private sector to do more, for an investment surge, and he has recognized areas of past weakness like corruption – yet again. The Ministry for Economic Development has put forward alternative outlooks, one of continued reliance on natural resources, or innovation; in other words a conservative and ambitious growth strategy. If the Ministry’s assumptions are justified, Russia will be doing better than many in terms of GDP growth under either scenario over the next few years.

None of this threatens Putin’s ‘power vertical’. The various discussion groups sanctioned recently, such as the extensive and well qualified body which put forward a revised strategy for development up to 2020, were firmly instructed to keep off the political grass. There is room for improvement if some of their ideas were to be implemented. Going beyond the piecemeal and realizing some of the more ambitious targets that Putin has set would be difficult even if state leadership were the best way of achieving them: the machinery is corrupted and incompetent.

Investment rates are unlikely to improve radically – as Putin has demanded – without transparency, accountability, the rule of law and secure property rights. This is universally acknowledged but expected by no one. Significant structural change would depend on the establishment of such principles, and would threaten the interests of both those at the summit of the so-called vertical and those charged with implementing its policies. Such change would be difficult, too, for a substantial number of Russia’s ordinary citizens, and nothing has been done to prepare them for it.

‘Innovation’ and ‘modernization’ are of course favourite words for everyone, and Putin not least. They are also usefully ambiguous. They carry a heavy bias towards technological improvement in the official political discourse, including through foreign direct investment and existing enterprises. That restrictive approach will neither upset the status quo nor provide for Russia’s longer term evolution towards flexible and accountable government. Nor will it answer to the next President’s need to recapture his hold over the Russian imagination.

Making Concessions

Both political and economic change are interlinked; and dangerous and necessary if Russia is to develop as it deserves. Putin and Medvedev were shocked by the recent protests, but have apparently recovered their poise. The systemic concessions as to gubernatorial and municipal elections have been modified so as to subject them to a considerable degree of central control. If such control cannot be maintained tensions with regional or municipal leaders with their own legitimacy would have to be secured either by compulsion or reinvented and trusted constitutional mechanisms. (The Kadyrov model of devolved tyranny is a dangerous singularity).

Putin appears to have no new ideas which might enable him to re-establish himself as the director of events. That does not necessarily doom the next administration but it does make him and Russia more vulnerable to the unexpected. The questions of what or who may follow Putin together with what reliable institutions there may be to allow for fruitful evolution will become more urgent than ever. The sense that Russia is headed in the wrong direction is well established in the national consciousness.

For additional reading on this topic please see:

The Tandem: Where Next?

Flattering to Deceive? Change (and Continuity) in Post Election Russia

Russia’s Future: Outlooks for its Citizens and the West

For more information on issues and events that shape our world please visit the ISN’s Security Watch and “Whither Goes Russia in the Post-Soviet Space?”.