In his 2009 book Aesthetics and World Politics, Roland Blieker made some controversial observations. Traditional forms of IR theory, he argued, exhibit “a masculine [aesthetic] preoccupation with big and heroic events: wars, revolutions, diplomatic summits and other state actions.” This, he claimed, was “supplemented with the scientific heritage of the Enlightenment…[with] the desire to systematize, to search for rational foundations and certainty in a world of turmoil and constant flux.” As one form of representation among many, then, IR theory by definition has aesthetic commitments, but — preoccupied with the ‘scientific’ imperative of representing as ‘mimetically’ (and absently) as possible – it has usually been blind to them.

What then, we should ask, are these hidden aesthetic commitments? And what have been the consequences of hiding them? One way of getting at this is by considering the dominant spatial representations of the world—i.e., the world maps — with which traditional IR theory corresponds. A world map is a way of conceptualizing the human condition as a whole. Maps of the world may be especially relevant to the study of international relations because (as Chris Brown has written) the study of international relations seeks “to build theory on the broadest canvas available” – an orientation that is perhaps its distinctive feature.

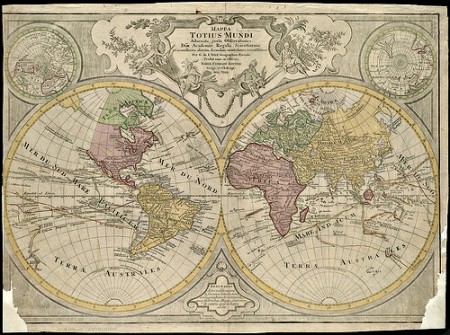

Today’s world maps are romantic; they suggest that what matters are the big and heroic: mountains, oceans, deserts, cities and national borders. And, in faithful positivist fashion, they seek to represent as ‘mimetically’ as possible, specifying magnitudes for mountains and cities and proportionally representing their relative positions. Some of the nicer globes even try to make the mountains the right height. A cursory survey of surviving medieval mappa mundi makes for instructive comparison. Some such maps already focus on the big and heroic, but a key difference is the treatment of space: not exactly absolute and homogeneous when ships, Krakens and the like are the size of Great Britain; and imaginary, undiscovered, or theological places exist alongside real, known, sublunary ones. The influence of the pictures of the world furnished by our globes and global positioning satellites on the pictures of the world furnished by IR theory is perhaps too obvious — yet remains poorly understood.