This interview was originally published by E-International Relations on 28 March 2016.

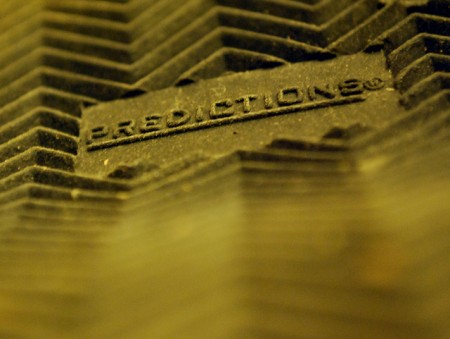

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita is the Silver Professor of Politics at New York University, director of NYU’s Alexander Hamilton Center for Political Economy, and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. He is an elected member of the Council on Foreign Relations and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was also a Guggenheim Fellow and president of the International Studies Association. He co-wrote The Logic of Political Survival (2003), The Predictioneer’s Game: Using the Logic of Brazen Self-Interest to See and Shape the Future (2009), The Dictator’s Handbook (2011), and co-authored the selectorate theory with Alastair Smith, Randolph M. Siverson, and James Morrow. He is an expert on international conflict, foreign policy formation, the peace process, and nation building. He received an honorary doctorate in 1999 from the University of Groningen and earned his M.A. and Ph.D. in political science from the University of Michigan.

How has the way you understand the world changed over time, and what (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking?

I began as a comparative politics, South Asia specialist with little formal training in international relations. Hence, when I moved into the IR arena I started from the perspective that system-level structural theories were the right way to study the subject. I stopped believing that with a set of papers I wrote in the late 1970s that highlighted the debate in the field over polarity and stability. I contended that the debates really were about how decision-makers respond to uncertainty. That led me to several conclusions that changed how I understood – or did not understand – how the international arena worked. First, since there were plausible arguments that multipolarity; that is, high uncertainty, led to cautious responses and alternatively that it led to miscalculations and misjudgments, I concluded that there was no inherent logical link between polarity and instability. Second, I concluded that variation in how states responded to uncertainty depended on who was in a leadership position and so we needed to study leaders rather than states, treating them as if they were unitary actors. I was particularly influenced by A.F.K. Organski’s Stages of Political Development (1965) in forming a view of how national decision making coalitions formed and William Riker’s Theory of Political Coalitions and his subsequent book with Peter Ordeshook. Their research exposed me to the possibility of rigorous logic as a substitute for opinion and hunches in studying politics. Grad classes with Donald Stokes also reframed how I thought about politics, especially after he exposed me to Von Neumann and Morgenstern.