This article was originally published by The Conversation on 6 July 2015.

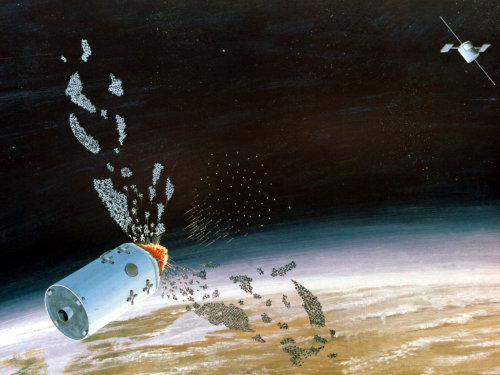

One thing was very striking at the recent Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) Land Warfare Conference, where current British Army personnel including top brass and Ministry of Defence officials were heavily present. The issue of replacing Trident, the UK’s sea-based nuclear deterrent, was not discussed at all.

This conference was taking place a few months ahead of Conservative plans to renew the deterrent like for like. This was guaranteed by the party’s victory at the general election in May, and has since been reaffirmed by Michael Fallon, the defence secretary.

Yet when it comes to Trident, the British military are “split on this issue as never before”. That was the conclusion of a report by the Nuclear Education Trust and Nuclear Information Service that was published at the end of June. So why the difference in views?