This article was originally published by IPI Global Observatory on 23 August 2017.

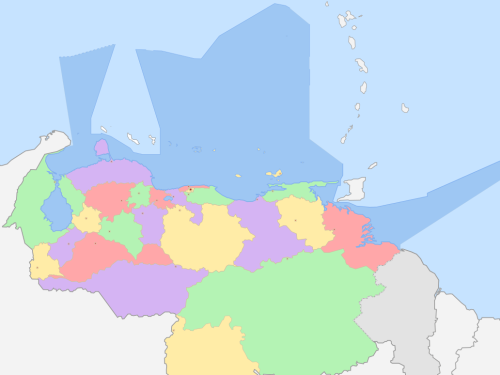

In 2013, Venezuela was a defective democracy experiencing serious breaches of civil and political rights, but with more or less functioning electoral institutions, and accountability between the branches of the state. Today, the country is an authoritarian regime. President Nicolás Maduro’s government crossed into that territory on March 29 this year, when the Supreme Court, following instructions from the executive, stripped the country’s National Assembly of its competences, triggering the wave of demonstrations that continues today (42 a day on average) and that has cost the life of 126 Venezuelans. Another definitive step occurred on July 16, with the election, through massive electoral fraud, of a Constituent Assembly with total powers over the National Assembly and aimed at rewriting the national constitution.

There are two main victims of the Venezuelan crisis. The first are the Venezuelan people, who have not only witnessed a dramatic deterioration of their living conditions, but have also lost the ability to live together in harmony, for an undetermined amount of time. The second victim, on which I focus here, is multilateralism—the ability of states to bring collective solutions to conflicts and crises through institutions and other forms of cooperation.