This article was originally published by the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) on 16 February 2017.

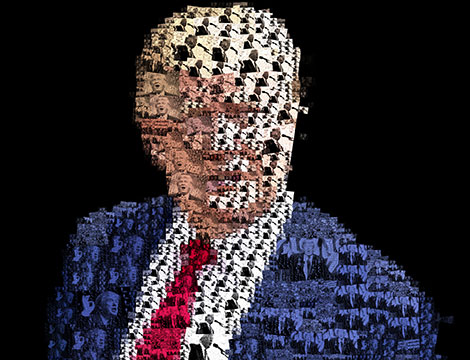

This week Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis delivered some tough love to America’s allies in Europe. Addressing NATO defense ministers, Mattis offered “clarity on the political reality in the United States.” If the allies do not want to see America moderate its commitment to them, he said, “each of your capitals needs to show its support for our common defense.”

On its face, Mattis’ call for NATO to spend more on defense is hardly new, and his words echo the public warnings given by former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and others. This year, however, after President Trump’s repeated questioning of NATO’s value, the allies are listening especially closely. The new administration is right to call for a boost in European defense spending, but the right measure of our allies’ value is in fact much broader. An overweening focus on budget metrics risks distorting, to NATO’s detriment and to America’s, what it means to be a good military ally.