When speaking of press freedom, Western European countries usually score highest in rankings from institutions like Freedom House or Reporters Without Borders. They are all declared as “free” with one notable exception: Italy.

In the 2009 report Freedom House downgraded Italy from “free” to “partly free”, highlighting worrisome trends that have been underlined by recent events.

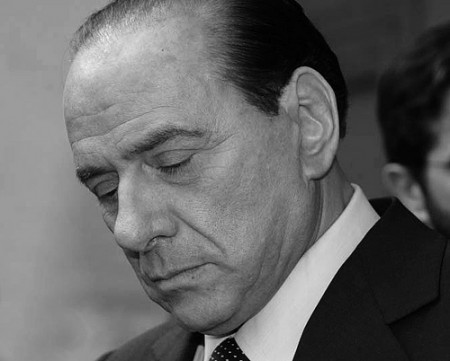

In February of this year four managers from Google Italy’s YouTube branch had to stand trial because of accusations regarding privacy violations. This was only one month after Italian officials proposed a new law against online copyright infringement which holds responsible companies that host and broadcast copyright protected content illegally (i.e. YouTube). Meanwhile, Google is still engaged in a similar legal dispute with Mediaset, a private media corporation controlled by Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi.

On 2 March 2010 the administrative council of Italy’s public television network RAI announced that two popular political talk shows will not be allowed to broadcast for one month until regional elections are over. State officials justified the decision by pointing to a law that guarantees equal opportunity of representation on public media channels to all parties. However, opponents argue that the decision is purely political as the two talk shows “Anno Zero” and “Balla-rò” have heavily criticized Berlusconi in the past.