This article was originally published by the Harvard International Review on 5 December 2016.

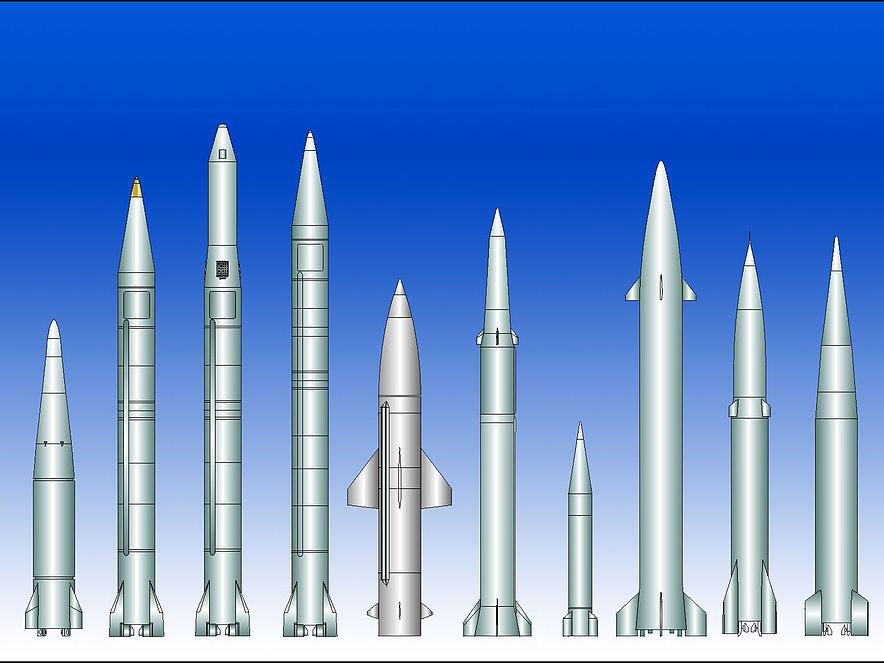

Since the atom was first split, the possibilities of war, terrorism, and proliferation have polluted the connotation of “nuclear,” driving public fear and associated dialogue surrounding the development of nuclear technology. In the last half of the twentieth century, the arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union defined the modern geopolitical layout of the world, from alliances to modern conflicts. Nuclear capabilities became one of the greatest criteria to determine a country’s power and respect on the global stage.

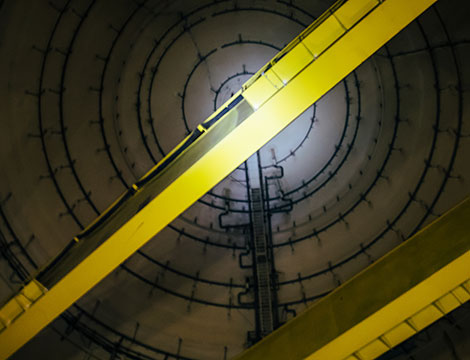

In this year’s US presidential election, the P5+1 nuclear deal with Iran was a divisive issue. The multinational agreement aims to prevent weapons development by fostering an officially recognized and heavily regulated nuclear energy program. This deal reflects a shift in the global nuclear narrative, from aggressive prevention efforts to diplomatic limitations. It further recognizes that as more states acquire nuclear development infrastructure, there will be more chances for materials to fall into the wrong hands. Preventing proliferation to terrorists, militant groups, and less amicable state actors is a global priority. Greater involvement and oversight from institutions like the UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) can facilitate better security standards for protecting nuclear materials.