This interview was originally published by E-International Relations on 15 February 2016.

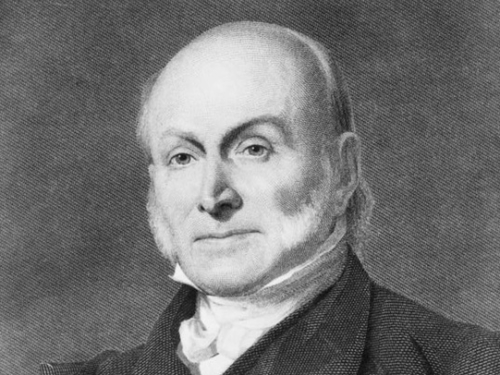

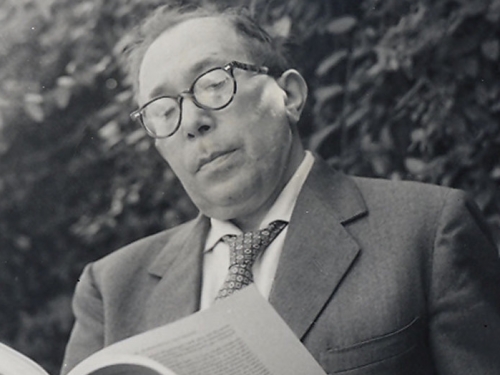

Richard Ned Lebow is Professor of International Political Theory in the War Studies Department of King’s College London, Bye-Fellow of Pembroke College at the University of Cambridge, and the James O. Freedman Presidential Professor (Emeritus) of Government at Dartmouth College. He has published over 20 books and 200 peer-reviewed articles in a career spanning six decades. Among his recent publications are Constructing Cause in International Relations (Cambridge, 2014);The Politics and Ethics of Identity: In Search of Ourselves (Cambridge, 2012); Why Nations Fight: Past and Future Motives for War (Cambridge, 2010); and Forbidden Fruit: Counterfactuals and International Relations (Princeton, 2010).

2016 marks your 50th year in teaching international relations. If you could encapsulate your career into just a few key events or milestones, which would they be?

I think the milestones would be the publication of my Between Peace and War: The Nature of International Crisis, which I worked on for 10 years. I put a lot of work into the case studies and the theoretical framework. It made my initial reputation in the field and also set in motion a program of researching the failings of deterrence as both a theory and strategy of conflict management and with that as well a critique of rationalist models more generally, so that very clearly was a milestone.