This article was originally published by IPI Global Observatory on 19 June 2017.

Forecasting political unrest is a challenging task, especially in this era of post-truth and opinion polls.

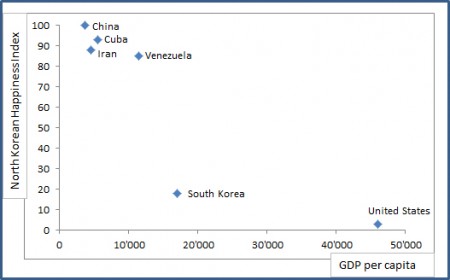

Several studies by economists such as Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler in 1998 and 2002 describe how economic indicators, such as slow income growth and natural resource dependence, can explain political upheaval. More specifically, low per capita income has been a significant trigger of civil unrest.

Economists James Fearon and David Laitin have also followed this hypothesis, showing how specific factors played an important role in Chad, Sudan, and Somalia in outbreaks of political violence.

According to the International Country Risk Guide index, the internal political stability of Sudan fell by 15% in 2014, compared to the previous year. This decrease was after a reduction of its per capita income growth rate from 12% in 2012 to 2% in 2013.