“Orthodoxy is experienced in debate and controversies, in those tacit agreements that are masked by overt disagreements.” – Ronen Palan, Global Political Economy: Contemporary Theories.

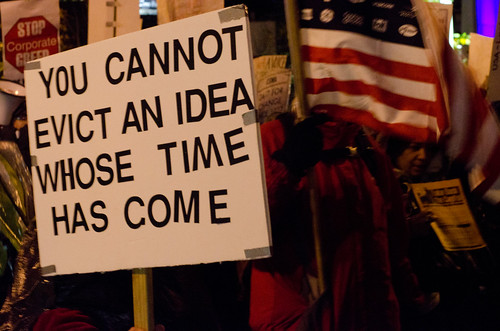

With the eviction of Occupy groups from their months-long encampments across the globe, and the cold of winter pushing people indoors, the general consensus was that Occupy had failed. Without long-term access to public spaces to practice their namesake tactic, few believed the movement had – or ever could – affect any meaningful change. However, this belief ignores the subtle ways in which the Occupy movement has come to, well, occupy our dialogue.

The Occupy movement grew out of a grumbling dissatisfaction echoed by youth around the world over broken promises from the increasingly globalized and interconnected economy. The broader concerns of the movement have resonated across the globe with people from all walks of life, and were reinforced through conversations over Facebook and Twitter. Every continent but Antarctica has seen its own version of the Occupy protests. Even recent protests that did not adopt the Occupy “brand,” such as the anti-Putin protests surrounding Russia’s elections, can point to it for both tactical inspiration and motivation, even if their specific goals may differ.

From Greece to Chile to the U.S., protesters spoke out against government policies such as austerity cuts, education policies, bank bailouts, and restrictions on internet freedom. With each step, the movement expanded the boundaries of what was acceptable criticism in our civic dialogue. Before Occupy Wall Street, there was little discussion of income inequality, underemployment, and living wages in U.S. dialogue about the economy. In Hungary, India, and Russia, corruption is under the microscope like never before. Protesters in Italy, Canada, and the United Kingdom are forcing a reexamination of the role of the state in support of the arts and university education.