This article was originally published by Oilprice.com on 1 February, 2015.

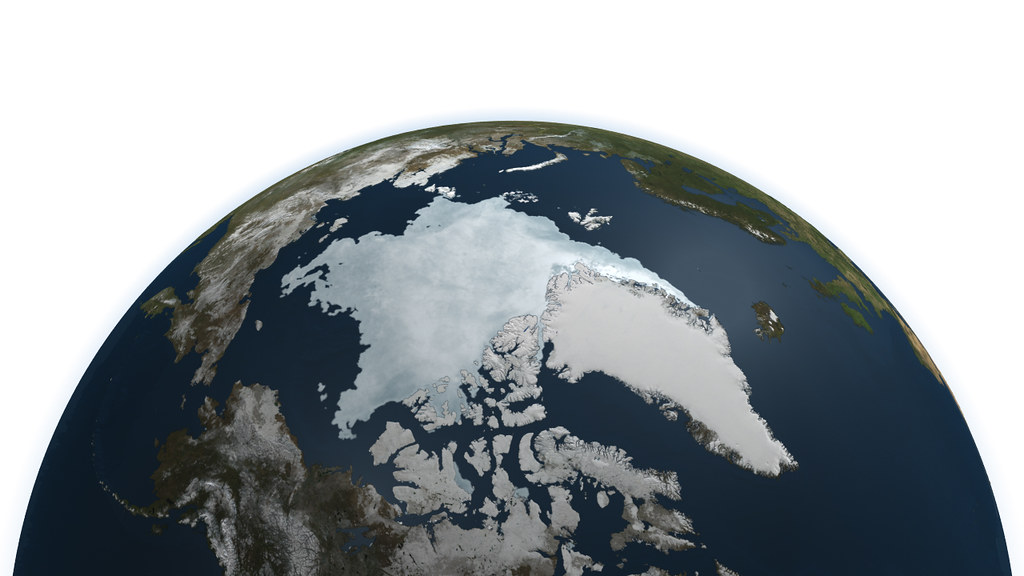

Oil companies have eyed the Arctic for years. With an estimated 90 billion barrels of oil lying north of the Arctic Circle, the circumpolar north is arguably the last corner of the globe that is still almost entirely unexplored.

As drilling technology advances, conventional oil reserves become harder to find, and climate change contributes to melting sea ice, the Arctic has moved up on the list of priorities in oil company board rooms.

That had companies moving north – Royal Dutch Shell off the coast of Alaska, Statoil in the Norwegian Arctic, and ExxonMobil in conjunction with Russia’s Rosneft in the Russian far north.