This article was originally published by ISIS Europe Blog on 25 July 2014.

The Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies and the Office for a Democratic Belarus had recently organized a conference on the subject of Belarus’ internal politics and its international position. “Why Belarus is different”, a “Food for Thought” event, took place in Brussels, on June 23rd. The importance of the topic for the EU states derives from the geographic proximity of the country to the communitarian borders and from the increasing instability in the Eastern European region, which could potentially expand its turmoil beyond the Ukrainian borders.

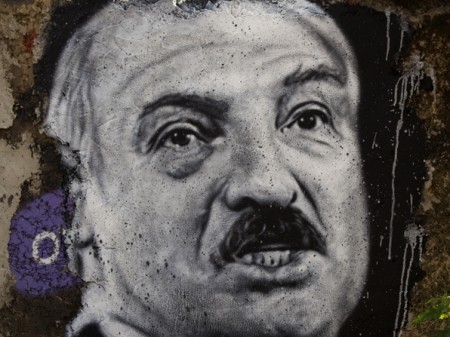

The first speaker and Senior Analyst at the Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies, Dzianis Melyantsou, focused on the current Belarusian domestic situation. He explained how, after the economic crisis hit the country in 2011, the population has lower expectations about a possible opening of the political scenario and actually manifests a higher appreciation for the current political establishment. President Lukashenko’s reputation has been growing since as well. Moreover, foreign businesses show a 22% growth in the appreciation of regime.

On the other side, 66% of Belarusians (two thirds of the total) do not trust oppositionparties, whilst only 16% of them do (namely, less than two out of ten persons). Moreover, just 3,6 % of the population would be in support of a revolutionary change in the country, although 25% of them would be ready to participate in protests against the government. When people are asked about the issues that concern them the most, the recurrent answers refers to healthcare, education and wages. The independence and functioning of the judicial system are mentioned only by a small 1% of the interviewed. Such numbers are accounted for by different reasons.

Firstly, the peace and order the regime has managed to preserve during two decades are highly valued by the local population, especially if coupled with the ongoing turmoil of the bordering Ukraine. Furthermore, Belarusians have not lived any democratic experience so far, and the recent Crimean crisis with its following events, could pose further doubts over the benefits of a political transition towards a Western-style society.

Moreover, the low level of visible or detectable corruption, the fading but still available benefits guaranteed by the social state, and the slow but constant economic growth the country has experienced have their weight on the survey results. It should be kept in mind that the elders and adults living in Belarus have never experienced levels of life higher than the ones enjoyed under Lukashenko presidency. They seem therefore not willing to put at risk the current economic stability for the possible benefits of a democratic representation.

Finally, the scarce accessibility to internet, the perceived lack of an alternative to conservatory and anti-liberal policies, and the fact that the opposition is entirely financed from abroad, all contribute to discourage a positive vision for alternative paths of governance. In that respect, president Lukashenko has proved keen at planning long term strategies and in constantly hampering any possible surge of movements perceived as hostile towards his government. The discussion continued with Siarhei Bohdan, Senior Analyst at Belarus Digest and Chief Analyst at the Ostrogorski Centre, who tackled Belarus’ foreign policy and neighbourhood.

He pointed out that the country is not geographically closer to the European core than to the Russian capital. Only 200 km away from Moscow, Belarus shares an open border with its powerful neighbour, and its economic and energy dependence on Russia makes it impossible to imagine any sort of agreement with the EU that does not take into account the important ties between such two neighbouring countries. A European solution supposed to exclude Russia’s weight would mean ignoring reality, and it would result in ineffective outcomes.

Cultural, economic and geographic proximity with Russia cannot be neglected and their links could not be cut off even in the case of a Belarusian rapprochement to the EU. Nonetheless, president Putin’s rhetoric regarding Slavic communities and the proximity between the Russian and Belarusian people should not impede analyses on the actual relations of such sovereign states beyond their leaders’ statements. Indeed, the speaker raised a problematic point: have we been assisting to a process of integration or disintegration between Russia and Belarus? In 1994, the latter was completely dependent on the former. Belarusian élites were confused by the sudden change of political paradigm. The state lacked the most basic infrastructure and its economic dependence on Russia was almost total: Belarus was a de facto dependent country.

Nowadays, the absence of a thorough economic integration and a missed comprehensive military and defence collaboration has led Mr. Bohdan to argue that president Lukashenko has actually brought Belarus further away from what once was the Soviet Union decisional core. The recent 2014 Trade Agreement with Russia and Kazakhstan perfectly exemplifies the speaker’s position, as it implies very limited consequences on the foreign policies of such countries. Minsk and Astana showed to be reluctant in conceding any part of their national sovereignty.

Regarding the partial military union between Russia and Belarus, it was realized only after a long delay and after the appointment of a Belarusian as the highest commander in charge. In addition, it was under president Lukashenko that Belarus joined the Partnership for Peace NATO program (in 1995), and it even has its own diplomatic mission at NATO (since April 1998). Finally, the Programme Officer at the European Endowment for Democracy, Jana Kobzová, provided the audience insights about the EU-Belarus relations.

She noticed how the EU has followed different strategies in defending democratic values in Belarus. Nonetheless, ranging from offers of cooperation with the Lukashenko governments to limited diplomatic and economic sanctions, such diverse approaches did not reach any positive results. Belarus is indeed the only Eastern Partnership country against which sanctions are applied, although Azerbaijan is arguably as authoritarian as Belarus and its human rights violation record isnegative. It appears that, in this case, the economic importance of the energy resources coming from the South Caucasus have led the EU to effect pragmatic political decisions avoiding strong condemnations of unlawful practices depending on the recipient state.

On the other hand, if the Belarusian governmental institutions seem to be unresponsive, its civil society (largely controlled by the political apparatus itself) appears to be equally out of the EU’s reach. Data shows that 50% of Belarusians are not aware of the EU sanctions targeting their country; the other 50% do not know why they are being implemented.

Such numbers are highly indicative of the distance that currently separates the common Belarusian citizen from the rest of the continent. Consequently, it is important to build bridges between the locals and the European Community.In addition, with the state managing the 80% of the economic activities, activists could be at risk of retaliations as regards their jobs, on top of potential direct judicial initiatives undertaken against them. None of the three speakers have actually put forward any credible path to a gradual approach of the EU concerning Belarusian grassroots realities.

In addition, as US’ interests are now redirecting to other major international contexts (such as the Middle East and the pivot to Asia), there is a lack of strong incentives to support the EU efforts for peace and stability in its Eastern neighbourhood. The twentieth anniversary of Lukashenko’s presidency, which took place on July 20th, is unlikely to be his last one. In terms of governmental policies, a continuation of the status quo is highly likely as well.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit ISN Security Watch or browse our resources.

Manuel Tornago is a Program Associate at ISIS Europe. He is currently completing a Master of Arts in Diplomacy at the VMU in Kaunas, Lithuania. Baltics security and

defence, EU energy-related topics and Russian foreign policy are among his major fields of interest.