This article was originally published by Radio Free Europe/Radion Liberty on 16 May, 2015. Editor’s note: Copyright (c) 2015. RFE/RL, Inc. Reprinted with the permission of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 1201 Connecticut Ave., N.W. Washington DC 20036.

Russian President Vladimir Putin got the world’s attention on May 10 when, during a joint press conference with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, he unapologetically defended the infamous 1939 nonaggression pact between Adolf Hitler’s Germany and Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union.

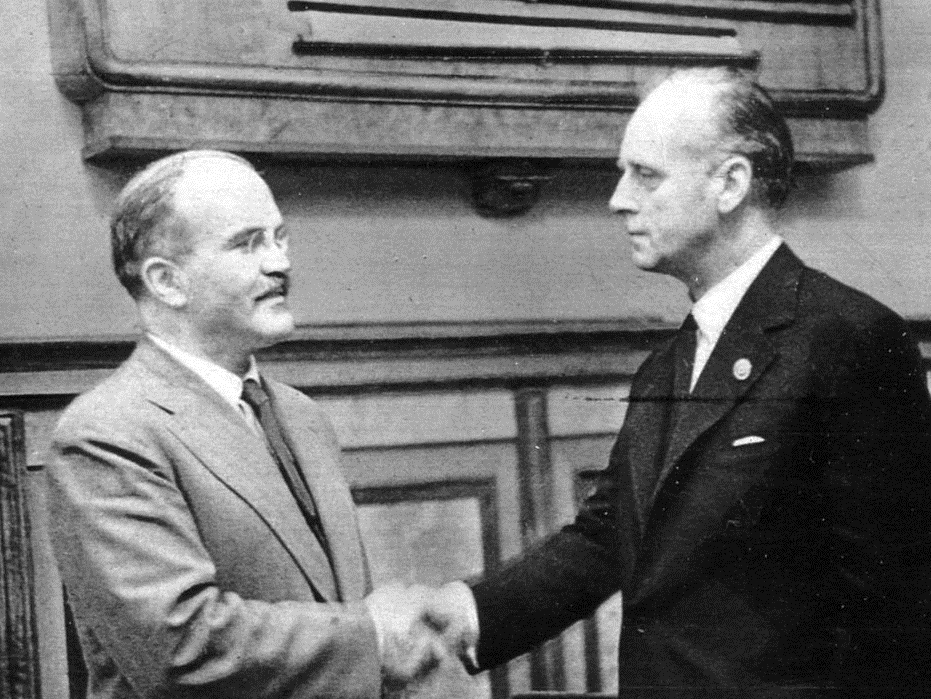

The so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact — named after the two foreign ministers who signed it in the late-night hours of August 23, 1939 — was formally a nonaggression pact. But it also encompassed a secret protocol under which the two dictatorships agreed to carve up Eastern Europe.